Chapter 3. Toward Axiomatic Morality

Our system of morals should be derived from a complete, self-consistent, mutually independent set of first principles that can be explained to a six-year-old and upon which most educated people can agree. If, in addition, those who dissent – even after we have employed our most compelling logical testimony – can be accommodated without coercion and without inconvenience to themselves or us, we shall have done very well indeed. – Chapter 1, above

Table of Contents

Toward the Elimination of Gray Areas from Morals and Ethics

The Statement of the Freedom Axiom

The Beauty, Reasonableness, and Practicality of the Freedom Axiom

The Corollaries of the Freedom Axiom

Corollary 1 Establishes Freedom To Dissent

Humane Treatment of Violators of Rational Morals that Tolerates Dissidents

Corollary 2 Prevents Inequality of Status

Definition of Status and Its Implications

Corollary 3 Establishes the Moral Necessity To Share Material Wealth

Drawbacks of Inequality of Material Wealth

Definition of Proper and Improper Games

The Money Game as an Improper Game

Corollary 4: What If Everyone Did It?

Corollary 5 Specifically Permits Abortions and Drug Use

Theorem 1 Establishes the Immorality of Material Compensation for Economic Deeds

Theorem 1 Disqualifies Employment as an Institution

The Rights of Members of Social Links

The Rights of Children As Individuals

The Rights of Children As Animals

The Rights of Children As Sovereigns

The Theorem Concerning the Treatment of Children

A Quasi-Steady-State Environment

The Basis for the Environmental Axiom in the Three Criteria

The Necessity To Control Population Growth

The Environmental Axiom as a Corollary of the Freedom Axiom

Exclusion of Unfalsifiable Statements

Mathematical and Logical Truth

Empirical Truth: Verification and Induction

Scientific and Historical Truth

Probability, Macrofacts, and Microfacts

Must Be Said with a British Accent

Truth about Events in Our Own Minds

Truth about Events in Other People’s Minds

Additional Discussion for the Mathematically Inclined

What a Statement Is from the Existential Viewpoint

What a Statement Is from the Functional Viewpoint

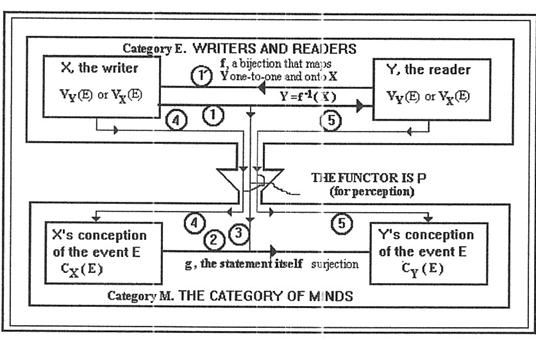

Analysis of Statements Using a Model Inspired by Mathematical Categories and Functors

Examples of Failed Communications, Usually Purposely Deceptive

Tarski’s Theory of True Statements

The Statement of the Truth Axiom

Justifying the Truth Axiom According to the Three Criteria

Immediate Corollaries of the Truth Axiom

Answer to the Puzzle about the “Little Town in Iowa”

Appendix: Why Taking Drugs Per Se Imposes on No One

Introduction

Disclaimer

In Chapter 1, I noted that we are far from that advanced state of affairs where legislators would be unnecessary inasmuch as anyone with an inference engine (computer and appropriate computer program) could test automatically whether a given proposition was a “law” (or not) by deriving it (or its contradiction) from fundamental axioms or first principles. Presumably, we could dispense with the inference engine if we could agree upon a basis. I hope to convince the reader that reasonable morals and ethics are simple. At least the simple morals proposed here are reasonable! Perhaps simple morals are more likely to be rendered reasonably. As complexity increases, so does the opportunity for mistakes in logic. The American legal system is complex to the point of madness.

Nevertheless, it is unlikely that I shall be able to derive rigorously, in the space of a few pages or even in a thousand pages, a complete, self-consistent system of morals based on three axioms that can be stated without ambiguity; so, this chapter must be taken to be a very rough sketch indicating only the direction such a derivation might take. Hopefully, though, an open-minded reader might accept the plausibility of such a project and our mutual understandings of the intuitive meanings of some of the basic terms employed here might allow this discussion to serve as a common basis for developing an acceptable political, economic, and social philosophy based upon morals.

As discussed in Chapter 1, I call this philosophy a minimal proper religion (MPR). (I have employed the word religion to accommodate people who insist that all moral judgments are religious in nature. Whether my moral philosophy is a religion or not is unclear.) It is supposed to be the basis of a rational social contract that has a decent chance to be embraced by an entire community (except for a few dissidents), in which case the members of the community are governed by moral consensus rather than by laws. They can live in peace and harmony essentially without government.

[Note in proof (6-26-97). I mean government in the conventional sense. Of course, the entire community may meet from time to time on an ad hoc basis to decide by mutual consent matters that affect everyone, which might involve flipping a coin to resolve disputes and, occasionally, selecting by some random process an ordinary, undistinguished member of the community in whom special responsibilities are to be entrusted temporarily. Under these circumstances, a common body of assumptions is even more essential than it would be in a modern coercive government. Since, quite generally, the governed may not exercise freedom that is in conflict with governmental policies, all modern governments are totalitarian. Perhaps readers who do not agree with this “extreme” view will wish to reconsider later – after further discussion (and, hopefully, a little personal reflection).]

The philosophy described in this chapter and the next should be recognized as something that has a much stronger claim upon the term social contract than anything that has been palmed off on the people previously under that banner. In the United States, what influential people call “our social contract” is certainly not deserving of the name.

Also, although this document attempts to follow the procedures of pure mathematics, it is impossible to prove propositions completely rigorously as one would do in abstract algebra, for example. The most we can hope to do is prove our claims as rigorously as social propositions are ever proved.

Of course, my moral sense did not arise from a set of axioms. I know a priori what the morals to be derived should be. The axioms stated below were abstracted from concrete examples (actually from my personal moral biases, discussed below) using what I have come to know as the inverse method. (These biases are revealed in the next subsection, at least in part for the benefit of both my friends and my critics to make it easier to refute my thesis.)

Note. Religious people might agree that Axiom 1, below, is a practical way of ensuring that people will behave as though they accepted the commandment “Love thy neighbor as thyself,” while Axioms 2 and 3 might be interpreted to exhort, “Love God with all thy heart and soul.” In this context “God” is supposed to encompass Nature and Truth.

Although I have rejected the Christian Science definition of Truth as God, I do regard Truth as something we might worship – where “worship” is taken to be a high degree of respect congruent with appropriate behavior in one’s everyday life. Suppose we behaved as though Truth were watching us and listening to our minds constantly and knew every deed, every pre-verbal thought or inclination whether voluntary or not, everything (as discussed in Chapter 1) in the universe (U), the ideals (I), the relations (R), and mind (M) pertaining to ourselves however remotely connected. Suppose nothing mattered to us except how Truth might judge us now and until the end of time. How would that affect our frivolous and wrong-headed inclinations each of which goes into the record of Truth along with everything else never to be forgotten or erased? Hopefully we would know better than to beg favors from Truth, but we do not beg favors from God either, do we!

Toward the Elimination of Gray Areas from Morals and Ethics

Nowadays, we have a large contingent of scholars, intellectuals, academics, and quacks who are representing themselves as ethicists. Ethics is portrayed as an unending series of deep and complex issues – each one requiring delicate weighing of facts and circumstances with the wisdom of Solomon. The “experts” continually refer to so-called gray areas that no tried-and-true set of precepts can subsume. To unravel these enigmas we require the expertise of specialists with years of experience at medical ethics, environmental ethics, business ethics, and so on. How convenient for educated people with no talent or interests! The “professional” ethicist is trying to build a castle of sand on a thoroughly eroded shoreline of cultural tradition that has been under water for at least ten thousand years and counting.

One cannot base a valid ethical system on tyranny, falsehood, and a complete misunderstanding of man and nature. Religion, as we know it, i.e., improper religion, is the primary culprit. When Moses, for example, went to the children of Israel and announced that he had spoken with God, Himself, and that he was prepared to pass God’s commandments from God to man, he was lying through his teeth; but, as is generally the case among Westerners (at least), he imagined that the end justified the means. He thought that a just cause justified any means whatever.

I believe that it is possible to think deeply about ethical situations and see the bare bones of situations without the complexity. I believe it is possible to assess every ethical situation in terms of three or fewer moral axioms without any gray areas arising.

Imagine what that could do for humanity. It renders laws, legislators, judges, and police obsolete. It makes rational anarchy possible. My PhD thesis advisor, Prof. J. D. Seader informs me that many years ago a man claimed that, if we learned the right morals, we could dispense with government. That man was none other than Joseph Smith. Nor do I imagine that Smith was the first to recognize this simple fact of life, which renders government, which most of us don’t like anyway, unnecessary. Of course, we shouldn’t expect to be satisfied with Joseph Smith’s system of morals.

The task I set before the reader, then, is to assess my ethical system and determine if it is consistent and exhaustive. (I drop the goal of mutual exclusivity (independence) as not worth the trouble to strive for. One can make an extremely compelling case without such niceties.) I would appreciate feedback on this, because no one knows better than I that I could have made a mistake of commission or omission. The challenge is to construct a thought experiment in which a situation arises that is not covered by the moral axioms proposed in this chapter or where so-called gray areas arise. I am waiting.

The Author’s Personal Biases

Why should the readers of this essay care about how my ideas got started? To be honest, I don’t think they should; they should judge my arguments according to the merit of the arguments without regard to who is making them or why. But, some readers might wonder what in the world would make a person think like I do. They might wish to dismiss my arguments as the ravings of the product of a disturbed childhood, thereby employing the well-known ad hominem fallacy. I will not give them my life’s story (just yet); but, to aid my critics, I will reveal my earliest impressions concerning the issues under consideration. These are prejudices and biases I picked up without the benefit of rational thought – really just feelings. This essay is supposed to justify those feelings, but the reader might find it useful to be told how my ideas got started. Many writers do not acknowledge that they are writing to promote beliefs that they had acquired without the bother of rigorous thought. The thinking was done much later if it was done at all. This is normal; nevertheless, I believe I give the reader who wishes to refute my conclusions an advantage if I reveal what my beliefs were before I began to think about them. I wish to be refuted if I am wrong, which leads to my first bias.

The Importance of Being Right

Some people think it’s unimportant whether they are right or wrong in their personal beliefs if those beliefs don’t affect directly their ability to satisfy tissue deficits or ensure the safety of themselves and those they care about, which may be very few. To me, being right is not just important, it’s the most important thing in life. Hence this book. (I’m tempted to say being right is the meaning of life; but that would be inconsistent with hard agnosticism; so, I won’t be falling into that trap.)

Nevertheless, writing this book has enabled me to clarify what I believe and has resulted in dozens of changes in my philosophy. Whereas some people think that “whoever has the most toys at the end wins”, I think that whoever has the best philosophy “wins” – if, indeed, life is a sport – as an ubiquitous television commercial in May (the month of the National Basketball Association playoffs) of 1995 would have it. (Television commercials have been telling lies about their products for years; now they have the temerity to spout bad philosophy. How about this one: “You don’t have a right to be thirsty because you have a right not to be thirsty.” [quoted loosely from Gatorade commercial] Wow!)

This need to be right might be irrational. It probably doesn’t matter to anyone but me whether I am right or wrong; and, on my deathbed, it might not even matter to me! My critics will say that I’m merely a conceited, self-important individual full of foolish pride.

Inequality of Wealth

I have never understood why people persist in wanting to enjoy greater wealth than others. Even as a small child I was often ashamed of having more than some of my classmates. I can understand how, in a moment of weakness, we can feel unjustifiably proud of having more wealth than others or even of having parents that do. It’s happened to me. But I still feel that it requires a defective mind to be able to sustain that attitude.

We do not approve of race, color, or gender, which are accidents of birth, as a basis for greater wealth. Why should we approve of intelligence, talent, will power, tenacity, ability to withstand tedium, industriousness, or even “superior” character, which are also accidents of birth, as justification for greater wealth? (We suppose character depends upon heredity and environment. The environment into which one is born surely is the same accident as the accident that selected one’s parents – for all we know.)

Why should an intelligent person who is highly gifted insist on receiving even more gifts as a reward for having received the priceless gift of intelligence? That’s just the way I feel. But, when, in addition to the ugliness of vast differences of wealth, I perceive highly undesirable social consequences, I am inclined to believe that differences in wealth must be immoral.

Bosses

I have never liked the idea of having a boss. I can safely say that I have never had a boss whose authority seemed valid to me. (I’m sorry, Henry, Howard, Alan, and Charlie. I love you all, but that’s how I feel.) I don’t know whether anyone deserves to be my boss or not, but I can’t believe that anyone else knows. If a worker needs advice or direction, he should select an advisor. It shouldn’t be necessary to beg for the type of assistance that good bosses sometimes give; I believe the old adage “beggars can’t be choosers” does not apply. Presumably, people other than the worker have an interest to see the work carried out. We ought to be accustomed to giving a little time to helping colleagues. Our peers will tell us when we are screwing up.

All through school, we are judged (basically) on how we perform on canonical tests. (It is true that what our teachers think of us influences our success slightly; but, in the face of written test scores, it is hard for teachers to discriminate blatantly.) When we leave school, however, our success depends on what someone else thinks of us. I can’t accept that. When I was an assistant professor, I announced that I would not submit to peer review for tenure. Isn’t it bad enough that someone can decide whether or not our papers are published and whether or not our proposals are funded!

I don’t like the institution of boss, manager, or leader – whatever it’s called. It irritates me that George Bush has more political power than I do.

Influence

Lately, I have attended a number of meetings – political, technical, philosophical – at which I have not been invited to speak. That bothers me. Why should someone else be asked to speak and not me? Are not my ideas as good as theirs? Who would know? Who reads the essays of an unknown? One has to “work oneself up” to a position of influence. That can’t be right. In many cases, by the time the thinker has worked himself up to a position of influence, he has succumbed to the routine of his life and his ideas have become pedestrian and anemic. Sometimes, the ideas of a person of influence have survived his ride up the prestige ladder; but, he has too much to lose to insist upon them in public discourse. For example, in the case of Noam Chomsky, he has brilliant ideas; but, because he has a highly valued position to lose (full professor at MIT), he must confine his remarks to criticism of the status quo, and may not tell his audiences what he would choose as an alternative economic system – except I believe I heard him mention in passing (only) anarcho-syndicalism, which I take to be a reference to his own political position. I have not read his books, which I recommend to the reader to corroborate my own ideas (but which I imagine I don’t need to read myself, as I am already a believer); so, I may be doing Professor Chomsky a disservice. If so, I apologize. [Note in proof (9-27-96). Lately, I have read three books by Herman and Chomsky [1] and Chomsky [2,3].] My point is that ideas should be judged on their own merits – not according to who holds them. Thus, the system of discourse is badly flawed. I resent that and intend to do whatever I can to fix it. If I should ever become a person of influence, I hope I remember what I am saying now. Unfortunately, I would most probably become like everyone else of influence, namely, a complete idiot. I’m sorry, but that’s my prejudiced point of view.

Business and Jobs

I have never liked business and commerce. My father was a businessman. His work seemed boring and inconsequential. I resent the business parasites who drive around in German cars with telephones. (I don’t need the driver next to me getting a margin call in rush-hour traffic.) Businesspeople make life difficult for me because they cause money to have more importance than it deserves.

Don’t tell me business creates jobs. Let us consider the principal factors in a person’s engagement in an economic enterprise: (i) the impact upon the environment, which might be quantified in terms of emergy consumed; (ii) the usefulness (to living creatures) of the items produced; (iii) the effort put forth and the time expended by the participant; and (iv) the reward received by the participant. The first two items represent precisely what is crucial in sound economic thinking; the last two items have virtually zero impact upon the preservation of species, whereas they are the first things that people consider when they think of economic enterprises as jobs! This illustrates the essential impracticality of the institution of employment as we know it.

Business doesn’t create anything; it only consumes. Therefore, the concept of job must be flawed. Imagine. Selling the time of one’s life! Where is the merit in creating jobs – an activity about which exploiters of the labor of others like to boast! The most prominent effects of jobs on society are undesirable. A job prevents someone from contributing to the common good without being exploited. Jobs poison intrinsic motivation. They destroy opportunity rather than create it. Personally, I hate jobs!

The Freedom Axiom

Personal Sovereignty

Definition (Rights). Rights are (i) freedoms that don’t violate accepted morals and (ii) entitlements that are guaranteed by accepted morals.

The personal sovereignty of adults is assumed and is not in question. In the absence of better information, we must assume that every new arrival to this universe is the lord and sovereign of his or her own being, and our earliest memories seem to indicate that the new arrival shares that view. One’s sovereignty over one’s own being is a right. Determining who enjoys personal sovereignty is an important part of the Freedom Axiom. We mention personal sovereignty here to motivate the next section, The Purpose of a Human Life, which could have been derived rather than assumed; but the derivation would have rested directly upon the Freedom Axiom, which itself is assumed but is shown to pass the tests of aesthetics, reasonableness, and utility.

[Note (12-9-04). With respect to the debate over abortion, which has subsumed genuine political issues in electoral politics, the moral issue is not the beginning of human life but rather the beginning of human rights. Clearly, human rights begin with the severing of the biological connection to the mother and not before.]

One wonders whether personal sovereignty extends to animals and even, perhaps, to plants. I refuse to discuss the sovereignty of plants here, mainly because I do not wish to appear crazier than I am, except to say that the idea is not absolutely out of the question. The question of the sovereignty of animals remains open. Personally, I regard animals as belonging to themselves, but I recognize that this would be a difficult point to sell to a cattle rancher. I rarely ask the permission of pet owners to address their pets, as I regard dogs, cats, and horses as people. Perhaps this is going too far. I do not insist upon it. After all, it is very difficult to protect rights that cannot be exercised.

Newborn babies, though, are entirely helpless and dependent on other people for survival and, therefore, are unable to protect their sovereignty. Does that mean that their sovereignty is invalid? If that were so, one could infer that the sovereignty of the weak is always at the mercy of the strong, but that would violate our derived sense of morals, as we shall make more definite in the sequel. In the system of morals described here, we protect animals (other than human beings) under an environmental axiom without insisting upon their personal sovereignty, but we establish the personal sovereignty of human beings under the Freedom Axiom. In particular, we insist upon the personal sovereignty of children and adults in order to determine how they are to be treated when they are in conflict with the rest of society and all other moral options have been exhausted. (This is not quite the case for very young infants incapable of reason. Their personal sovereignty is held in custody by their parent(s) or guardian(s) and they are protected from their parents and guardians by the moral axiom that prohibits cruelty to animals. This makes more sense when the details are discussed below.)

The Declaration of Independence states that the right to liberty, which is intimately connected to personal sovereignty, is unalienable. (The modern spelling in inalienable.) This legal term means the right cannot be transferred to another person nor can it be repudiated. The Ninth Amendment indirectly incorporates this right into the Constitution; so, under the Constitution, we are free whether we want to be or not! However, I do not believe this inalienability extends to small children and I don’t believe that the Founding Fathers intended it to. I assume that newborn children temporarily transfer their personal sovereignty to their parents or guardians automatically and, presumably, voluntarily with the first whimper for succor. Older children may transfer personal sovereignty deliberately. The asymmetry between adults and children typically creates moral complexities. I believe we have unraveled these complexities in this chapter and the next two chapters.

Although the Founding Fathers are stuck with what they wrote, the Supreme Court notwithstanding, I am not. Even though I do not accept the Constitution in any permanent sense, I am entitled to use it to point out the inconsistencies of people who do believe in the Constitution but violate it routinely. Perhaps, the political philosophy expounded here requires a new constitution – without elected officials, for example. On the other hand, perhaps no document whatever would serve us best.

Definition (Personal sovereignty). Personal sovereignty is complete control over one’s own mind and one’s own body and its interior, defined so as to include the digestive tract, the interior of the head, etc., in analogy with the supreme and absolute power of a king or queen over his or her domain. Personal sovereignty permits the individual who possesses it to enter into treaties and contracts with individuals, with society, and with social institutions or to refuse to do so and to continue to be treated with respect.

The Purpose of a Human Life

It is assumed in this essay that a human being is the sovereign of his (or her) own being, not a beast of burden the purpose of which is to serve another, presumably superior, human. Whereas a human being may wish to serve others as a manifestation of his (or her) nobility or “to serve God” or some higher purpose in order to transcend himself – from the viewpoint of worldly affairs, he is basically his own person, an end in himself, not a means to an end. Man has been searching for the meaning of life for a long time and many people believe they have found it, but no one can present incontrovertible evidence that would be acceptable within the philosophy discussed here to permit these findings to be applied to public affairs. Perhaps man does serve some higher purpose, and I believe that he does, even if that higher purpose be no more than his own personal conception of the transcendent; nevertheless, no one may assume that a higher purpose exists and, more important, no one may attempt to impose his conception of the function of man upon other people or upon society. The purpose of man and the meaning of life are private matters.

[Note. I had something very definite in mind when I wrote “personal conception of the transcendent”. Clearly, the sum total of a person’s thoughts, words, and deeds exists as a spiritual entity since it can be conceived of, stated in words, and communicated to another person – in principle. This is something that exists. If we could step outside of space-time into whatever space-time is embedded in, if such a thing exists, this entity might be observed as an object, a string of events. This object whether spiritual or material can have meaning. The meaning is transcendent and might be taken by a human being to be the purpose of his life. Clearly, we are free to assign meaning to life in any way we choose or not at all.]

But, people who wish to give a person a purpose other than himself are typically interested in his function as a part of an economy, or as the defender of a nation, or in some other capacity that is not in his best interests. It is this function that is rejected here. This is a humanistic philosophy. We hope to put an end to the exploitation of people as a means to an end. Further, we hope to show that this exploitation is not only immoral but a recipe for doom in keeping with our other demonstrations that from evil comes nothing but more evil – certainly nothing sufficiently good to overbalance the evil. (I am assuming that the “litmus test” of Matthew 7:17,18 can be applied to any institution – not just prophecy. “[B]y their fruits ye shall know them.”)

The Statement of the Freedom Axiom

Definition (Freedom). Freedom is the exemption from external control, interference, regulation, etc. It is the power of determining one’s own actions or making one’s own decisions. These are dictionary definitions; but, for political purposes, there must be a temporal component to the definition. The exemption from external control, for instance, must be in perpetuity. Political freedom must include freedom from fear that the freedom can ever be abridged.

[Note in proof (1-12-98). Perhaps the word autonomy would have been a better choice for this essay. Clearly autonomy is a necessary condition for freedom. The dictionary assigns many more meanings to the word freedom than it does to the word autonomy even though the two words are synonymous! I feel the word freedom is somewhat more compelling, though; and I am willing to take the trouble to disqualify freedoms that impose upon the freedom or autonomy of others. The definition of happiness adopted from Deci and Ryan [5] employs the term autonomy (as a condition for happiness).]

Note. As discussed by Deci and Ryan [5], freedom involves internal conditions as well as external conditions. Normally, people who are involved in the competition for wealth and power are acting under psychological conditions that preclude freedom. In the language of Deci and Ryan they are extrinsically motivated. We are sorry that rich and powerful people are not truly free, despite the relative freedom that comes from their large compass of movement, but we are sorrier still that they prevent us from being as free as we should be, regardless of our internal psychological state. The truth may make us free to some extent, but it cannot grant us access to the beach at Malibu except by an unacceptably circuitous route. We may not be held by fetters of our own making, but we cannot view the most beautiful portion of Paradise River unless we are members of the Plutocrat Hills Golf Club.

Definition (Adult human being). An adult human being is a mentally self-sufficient (human, not animal) person. (At this point I don’t want to cut it any closer than that.)

Definition (Child). A child is the offspring of a human being still dependent on and, normally, living in the abode of natural or surrogate parents.

Note. We have omitted the case of (human) people who are neither children nor adults.

Definition (Human social link). A human social link is an adult human being and any dependent children.

Axiom 1 (The Freedom Axiom). The adult members of human social links are free to do anything they please provided they do not impose (in the present or in the future) upon the freedom of other human social links. (Nearly everyone agrees that his (or her) freedom ends at my “nose”, however many people disagree as to what “impose” means.) Further, the adult members of human social links possess personal sovereignty, which is nontransferable (inalienable), except when they permit their personal sovereignty to be placed in the custodianship of others under the exceptional circumstance that they have violated morals or rights to which they subscribe. Adult members of human social links are the custodians (or co-custodians) of the personal sovereignty of children in their social links until the children reach the age of reason. They may transfer the custodianship of that personal sovereignty to other adults from time to time provided the rights of the child be not abused. After children reach the age of reason, they may elect to leave one or more of their human social links and reclaim their personal sovereignty or to remain in one or more of their human social links and to transfer voluntarily their personal sovereignty to the relevant adult(s) who continue(s) to hold it in custodianship or stewardship. Up until the time the child reaches the age of reason it belongs to the same moral category as animals and is protected by Axiom 2, below.

Definition (imposing upon the freedom of another human social link). If an action interferes with the freedom of another social link but it would not if the members of that link adjusted their mental outlooks appropriately without any other adjustment being made, no violation of Axiom 1 has occurred; i.e., this does not count as imposing upon the freedom of another human social link. If their mental outlook is irrelevant, it counts as imposing upon the freedom of another social link. The point is that we wish to disallow imaginary offenses. For instance, if I can’t go to the Plutocrat Hills Country Club, I can adjust my mental outlook to disparage such a trip, but the fact remains that I must adjust my travel plans as well as my mental outlook. On the other hand, a man’s homosexuality may distress his own mother, but that is because of her attitude toward homosexuality. It does not impose upon her freedom.

Comment. The previous definition explains why this code of morals forbids trade and unlimited reproductive rights, but does not forbid taking drugs and having whatever forms of sex one pleases (so long as an axiom be not violated). An extremely compelling reason for accepting my interpretation of the Freedom Axiom as opposed to the interpretation of the Libertarian Party, say, is that my interpretation eliminates all, or, at worst, nearly all, of the problems that plague society, whereas the interpretation that tolerates commerce, for example, exacerbates social problems. It is no use saying that, if we cannot engage in business, we are not free, because, if anyone engages in business, no one is free. This will be proved by explicit examples in the sequel, even though the a priori reasoning given below is conclusive. (“It is impossible to provide an excessive number of proofs of a proposition that no one believes.”) Clearly, this is a crucial point in my thesis. I must convince the reader that doing business imposes upon the freedom of those who cannot or will not do business – particularly those who do not wish to do business. I will go further and show that it diminishes the freedom of the businessman himself. In Appendix III at the end of the book, I will discuss further why business is immoral but taking drugs is not. I shall attempt to overcome all reasonable objections to my viewpoint.

Rather than provide a philosophical basis for the Freedom Axiom, in the following section I shall defend the notion of equality of personal material wealth, power (including negotiable influence), and negotiable fame. This will turn out to be equivalent to such aspects of the Freedom Axiom as are not readily accepted by nearly everyone, namely, the prohibition of impositions upon ourselves by others and upon others by ourselves, concerning which the conventional wisdom, indeed our entire culture, is curiously silent.

The Beauty, Reasonableness, and Practicality of the Freedom Axiom

Aesthetics

In Chapter 1 we agreed that morals should be based upon aesthetics, reasonableness, and utility. Let us indicate in part how these values can be used to justify Axiom 1. (It is important to attempt to justify the moral axioms by the most convincing arguments we can construct since the fate of the political system proposed in this essay might depend on the acceptance or rejection of the moral axioms.) Clearly, we shall have established the Freedom Axiom if we can make a good case for equality; all the rest is obvious.

Many thinkers and writers, particularly American thinkers and writers, have espoused the equality of all “men”, and yet many of our institutions ensure that such “equality” as we do enjoy shall be meaningless. Presumably equality appeals to us on aesthetic grounds, but we do not construct our institutions always with aesthetics in mind. Axiom 1 espouses ultimate symmetry between adult men and women, while, unfortunately, retaining some unavoidable asymmetry between children and adults. Our love of symmetry is an essential component of our sense of beauty. Even when we avoid it, as when an object in a photograph is placed off-center, the variation calls attention to the underlying symmetry that is intentionally avoided! We build cars with bilateral symmetry just as we ourselves are built, although the symmetry is never exact. In mathematics, symmetry is the underlying concept at the heart of abstract group theory which is at the heart of abstract mathematics. Mathematicians love symmetry for its beauty.

Reasonableness

But, equality among human beings appeals to our sense of what is reasonable. No matter how talented, intelligent, or gifted a person may be, he (or she) ought to recognize that he is no better than other people. Normally our instinct warns us that people who think they are better or more deserving than others lack genuine respect for themselves, which might be evidence of something often referred to as the “inferiority complex”, whether such a thing exists or not. Indeed, equality is more appealing to us than is disparity on the grounds of both aesthetics and reasonableness. Furthermore, those of us who understand the fundamentals of mathematics know that the relations “less than” and “greater than” cannot be applied to a class of objects unless they possess certain properties that humans do not possess. (The problem with applying the relations “greater than” or “less than” to human beings is not that they possess too few attributes but rather too many.) Thus, we cannot establish a reasonable basis according to which one person deserves more freedom, wealth, power, or, really, anything else of value than another. In absence of any such basis, the only relation that makes sense is equality. As Shaw points out, no one person can point to the share of the national dividend that was produced by himself. Moreover, no one can assess the potential contribution of a person who is given his fair share of the national dividend until that person’s life is over – and perhaps not even then.

Utility

But, Axiom 1 can be justified based on its utility and the impracticality of any other moral judgment. The proof of this is the thrust of much of this book. We wish to show that inequality among people is the cause of crime, war, and most other forms of social disorder. Most of us recognize that this is so, but we cannot see our way clear to embracing the idea wholeheartedly. This is mainly because we do not believe in the essential goodness of mankind or even the essential goodness of the universe in which we live. This is shocking and certainly worth serious consideration. Since I shall be devoting many pages to reasons why it is impractical to permit disparities in freedom, power, wealth, and even fame between individuals, I will not attempt to present much of an argument here except to note the following: The time is rapidly approaching when one dissatisfied person who feels he or she has been treated unjustly by society can wreak havoc upon society, perhaps even discharge a nuclear device. The rise in terrorism is a certain sign of this. Soon, people who impose upon the freedom of other people by virtue of greater wealth and power will no longer be safe in their own beds. Inequality will become very impractical indeed.

The Corollaries of the Freedom Axiom

Corollary 1 Establishes Freedom To Dissent

Corollary 1. No one shall force or attempt to force another person to embrace or to be bound by any morals whatever including these morals. Nor shall there be a penalty – direct or indirect, harsh or subtle – attached to the rejection of any moral system. Clearly, I do not share Mr. Shaw’s readiness to label people “eccentric” even, let alone “lunatic”.

Proof. Corollary 1 follows immediately from Axiom 1.

Definition of Justice

Definition (Justice). Justice is the state of human society wherein one of two conditions prevails: (i) all relevant moral requirements have been met or (ii) in case there has been a breach of morals the following events have occurred: (a) the damage due to the breach of morals has been repaired and restitution has been made to the victim(s) and (b) the violator has been dealt with in an appropriate manner, which might not involve punishment or revenge.

Humane Treatment of Violators of Rational Morals that Tolerates Dissidents

Compensation of the victims of injustice is insufficient and, in some cases, impossible. We shall be concerned here with the treatment of violators of valid morals and we must decide what is appropriate treatment for violators. The cases of adults and children must be handled separately. We will discuss the case of children who violate laws based on morals after the axioms and their corollaries have been stated. Further, two subcases must be considered under each main case: (1) the case when the violator accepts the code of morals and (2) the case when the violator does not. Let us consider the normal case first, where the violator is an adult who accepts the code of morals and, in fact, expects to be protected by it.

For those who accept the prevailing

morality, but are

given to transgressions of it, a humane form of rehabilitation can be

found

that does not compound the felony with cruelty or any further suffering

by

anyone. I hope the reader

understands that I am uncomfortable with a discussion that raises the

specter of punishment. Presumably,

the culprit’s acceptance of the social contract permits us to

dispense with

punishment and to give the remorseful transgressor a chance to suggest

the

steps that will help him fulfill his sincere desire not to repeat his

mistake.

Clearly, I am reluctant to punish those who act out of fear of greater

poverty

than anyone can reasonably be expected to bear. This

circumstance would not

arise in hypothetical world ![]() , discussed in

Chapter 1.

, discussed in

Chapter 1.

On the other hand, I have suggested (in an earlier essay) that so-called white-collar criminals be reduced to the lowest economic stratum in society, i.e., minimum wage, which has the interesting property that the punishment becomes (nearly) meaningless at the same time as the crime becomes (nearly) pointless, namely, when material wealth is divided equally, that is, when the minimum wage is the maximum wage – or, better yet, the concept of wages has been abandoned. The reader should understand that I am not recommending jail for such criminals. (Ivan Boesky is in jail at this writing, but he is still a very wealthy man. This is stupid and unfair.) I tend to be much less tolerant of crimes that appear to be motivated by greed, but I suspect lately that these earlier sentiments reveal petty vindictiveness on my part of which I ought to be ashamed. Still, it’s not a bad suggestion.

Some crimes, such as murder, will probably require isolation of the criminal from the rest of society. But, can capital punishment be justified even in cases of murder? Apparently, capital punishment is inconsistent with the definition of justice and the suggestion that murderers be isolated from the rest of society. If society revenges murder with murder, the possibility arises that a mistake be made in which an innocent person is executed for a crime he or she did not commit. This would be a violation of morals for which no reparations could be made and it would require the violator to be isolated from society. But, when capital punishment is employed unjustly, all of society is the violator. Since society cannot be isolated from itself, we have run into a contradiction that could have come only from the assumption that capital punishment is valid. (Obviously, all of society cannot be executed!)

This is the type of argument, referred to in the preface, that is conclusive but unsatisfying because of the disparity in scale between the reasoning and the conclusions. Other reasons for objecting to capital punishment are given in the essay “On Crime and Punishment” in Vol. II of my collected papers [6].

[Note in proof (5-17-97). The Houston Chronicle of May 14, 1997, reported the first instance in Harris County of the acquittal of a person accused of a capital offense. Probability dictates that many innocent people have been put to death. What are the odds that only the guilty are accused? Is it reasonable to suppose that the police will have carried out an investigation sufficiently thorough to satisfy every conscientious juryman? Is it not possible that our self-righteous, Bible-thumping, free-wheeling, gun-toting wild men of Texas prefer an execution to an acquittal?]

It might be objected that no reparations can be made to the victim of a capital crime. Regrettably, this is true; but, the killer was not in the business of dispensing justice, a role the State has reserved for itself along with the associated responsibility, which it does not seem to take seriously, at least not here in Harris County in the State of Texas. (I hope the reader does not disqualify me from this discussion because of the guilt I bear as a citizen of this unhappy place.)

While it is claimed that most individuals who accept the moral basis of society presented in this work can teach themselves to live within its bounds, a society of individuals all of whom belong to the same economic class would be able to afford to put up with a residue of totally worthless incorrigibles. A society from which institutionalized evil has been eliminated would not be plagued by continuous class warfare and a class of individuals who will do anything to acquire greater material wealth. Very few people would want to violate a just system of law. Most of the crime we see in 1990 derives from inequalities of wealth and the unacceptable circumstance of having two sets of laws, one for the poor and one for the rich. Why should anyone submit to this type of institutionalized injustice! Criminals and active dissenters are the only people with integrity under these conditions.

But, as I said elsewhere, intolerable breaches of morals must be treated as acts of war rather than crimes unless the perpetrator embraces the morals in question voluntarily. If a transgressor does not accept the moral basis of our social institutions, he or she must be treated as a prisoner of war rather than as a criminal, and as such is entitled to all of the rights and privileges of a prisoner of war, basically in accordance with the way officers would be treated under a liberalized Geneva Conference, i.e., they may not be forced to work, etc. To make certain that the rights of dissidents are respected no matter how bizarre their deviation from the norm, people who do not accept the prevailing morality must be permitted to live as well as, or better than, anyone. Extreme cases, in which isolation from normal society is essential, present special difficulties.

Islands in the oceans might provide suitable isolation from societies that are unacceptable to heteroclite individuals, provided their chances of survival without the aid and comfort of their fellow man, or all but those who share similar views, are as good there as anywhere else. To protect our own innocence and to avoid errors of the opposite type, we should provide such criminals with palatial residences, abnormally abundant material wealth, and, perhaps for our own selfish reasons, plenty of servants.

These “servants”, or, really, guards, have accepted the community social contract and are expected to behave accordingly. We can rely on them to keep us absolutely safe from extreme deviants, while, at the same time, absolutely prevent such people from suffering merely because they are different from us. Apparently, every society has expected “them” to suffer for not being “us”. This is an exceptionally cruel and unreasonable, but morally cheap, purchase of (worthless) self-righteousness for the majority culture. No one ever achieved virtue, let alone nobility, by punishing others. And doing it in the name of God won’t help. Man needs to emerge from the dark ages. It’s time to reject our atavistic natures – to be, at least, human, if not divine.

Thus, society must treat dissident criminals better than anyone else. In particular, we must provide them with their legitimate needs – really, whatever they wish. What was said above about captive heads of state goes. The person with his own moral code is the moral equivalent of a Napoleon. This is required by the necessity to respect the personal sovereignty of the individual according to the Freedom Axiom. In a natural economy this will not amount to a serious drain on our scarce resources because dissident criminals will be extremely rare – if any exist.

Corollary 2 Prevents Inequality of Status

Corollary 2. It is violation of the Freedom Axiom and therefore immoral for a person to attempt to gain ascendancy or to accept a position of ascendancy over another person other than his or her own child or the children of others who voluntarily transfer ascendancy over their children, thus political power must be shared equally by all adults.

Definition of Status and Its Implications

Discussion: Let us interpret power (we should say “metapower”) as the ascendancy of one person over another. Now, we have discussed how power can be converted to fame or money; fame can be converted to money or power; and money can be converted into power or fame. The reader can verify this for himself by choosing examples from among the powerful, rich, and famous. Wealth, power (including negotiable influence), and negotiable fame are occurrence equivalent. By means of this equivalence, we have shown that whatever is true of power is also true of money and fame (within the social context under consideration).

Excess power abridges the freedom of someone, although perhaps not everyone, who does not enjoy that margin of power, otherwise it would not be power. Therefore, since excess power is prohibited by the Freedom Axiom, so are excess money and excess fame. One may object that this argument depends on the exact equivalence of fame, money, and power; therefore, we should consider the use of direct arguments for eschewing power, money, and fame, although it is fame, probably, that will be the last to disappear from our culture. The harmful effects of our preferred treatment of those who enjoy fame, our so-called celebrities, are easy to discern. Fame, money, and power in any combination contribute to what we call status, rank, or, foolishly, “success”. There is no point in talking about self-esteem for the masses while some people are very much more important than others. Normally, we are not dealing with people of extraordinary spiritual depth who are virtually immune to the influence of social ambiance – what happens on TV, for example. The average American knows he is a person of no importance, essentially a “nobody”; and, if he forgets it, society is certain to remind him in a thousand ways.

Proof of Corollary 2

Proof of Corollary 2. To be in a position of ascendancy over a person constitutes an abridgment of that person’s freedom inasmuch as social transactions cannot be negotiated without coercion or, what amounts to the same thing, the possibility of coercion. This is a generalization of the free-market rule, which requires that all participants in free markets have equal power. (My use of the free-market rule in this context is not inconsistent with my rejection of free-market economies. The free-market rule is the justification for free markets. Paradoxically, it never holds true in actual market systems. This observation shows that there is an inherent inconsistency in the reasoning of free-market proponents.) Clearly, a person with greater political power than another could use that excess power to abridge the freedom of the other in many ways, or it might be feared that he could do so, which amounts to the same thing.

Management and Leadership

The institutions of leadership and management are the tools by means of which the domination of some people by others is legitimized in Western society. If we could not invalidate these institutions, we would be forced to abandon our thesis. We can distinguish at least four functions of leadership or management: (i) the planning of enterprises, (ii) communication between members of the same enterprise and between different enterprises, (iii) the determination of what will be done by each of the participants, and (iv) the creation of distinctions among individuals (as in a caste system). These four functions can be separated. The first function poses no threat of domination of one person by another. The selection of communicators could be accomplished by consensus or by some random or quasi-random process, but the removal of communicators could be accomplished by popular vote. Communicators could serve for fixed terms of from one to eight years, say, after which they could return to their careers. But no leader or manager may exercise power over another adult human being. The function of gifted individuals is to advise not control. The power over enterprises of production could be shared by the producers within that enterprise. Any educated person might be eligible to be chosen by a random process for temporary roles as communicators and almost everyone would be educated. The few exceptions might be termed formally uneducable. The fourth function is an outrage against humanity and any rational hypothetical deity one can name.

Formally Uneducable

Definition (Formally uneducable). By formally uneducable is meant the mentally handicapped, the incorrigible, and others the education of whom must be attended by unreasonable hardship, all of whom are to be distinguished scientifically. (This is a very dangerous point and great care must be taken to avoid abuses.) Of course, mentally incapacitated people are not mentally self-sufficient, so they are not properly classified as adults according to our definition.

Corollary 3 Establishes the Moral Necessity To Share Material Wealth

Corollary 3. It is immoral not to share wealth (both property and income measured in emergy units) approximately equally among adult human beings. Small differences in the wealth that surrounds us in our homes to account for special needs are not important. I don’t care if you have a microscope and I don’t. The vast accumulations of paper wealth and the correlative control of capital is the evil we wish to prevent. Of course, vast inequities in personal consumption are to be discouraged too.

Drawbacks of Inequality of Material Wealth

If one person controls greater wealth than another person, he (or she) perforce enjoys greater political power since he is in a position to trade some of his excess wealth for favors or someone might presume that he is able to so do. Thus, the freedom of the poorer man to choose his own political destiny is abridged without any other event taking place. Wealth is power and power can be transformed into freedom; thus, freedom is relative and the man with relatively greater freedom enjoys this margin of freedom at the expense of the freedom of the man with less freedom. Conceivably, this relative freedom is illusory and both the rich man and the poor man lose freedom.

Excess wealth might be a trap that restricts the movements of those who have it. It might be responsible for obligatory social rituals that the rich man must act out faithfully whether he wishes to or not. Also, whereas a rich man may know that he has accumulated X million dollars, he is well aware that X million is next to nothing in comparison to all that he might acquire. Thus, he may be seriously committed to a game that he can never win, since no one can tell him how much he might acquire with greater dedication and perseverance and, thereby, determine what exactly constitutes “winning”. Indeed, he knows that his pitiful fortune is despised by others more ruthless and persistent than himself. This could lead to suicide, even, if the frustration of playing an essentially futile game dominates his other thoughts. In any case, it is clear that the freedom of the poor man is abridged, therefore such differences in wealth are immoral.

It is not clear that a newborn baby should control the same wealth as a fifty-year-old. This might encourage childbirth, which might exacerbate overpopulation. The methods of sharing wealth suggested in this essay, both in the near term and far term, avoid this difficulty.

According to its definition, freedom requires absence of threats to itself. People with more wealth constitute a threat to the freedom of people with less wealth. Society supplies numerous examples that show that relatively greater wealth can be used by one person to abridge the freedom of another; for example, people with excess wealth might be able to purchase large portions of the earth’s surface and unfairly deny others access to it. This is a violation of Axiom 1. The mere existence of money forces people to perform tedious and dreary tasks, cf., filling out income tax forms, in which most people have no interest. This is tyranny. The above discussion provides reasoned arguments for Corollary 3, but we would like to have a brief and conclusive proof.

Definition of Proper and Improper Games

Definition (proper game). A proper game is a fair competition that satisfies generalized game rules: (i) the score is tied when the game begins, (ii) the rules are stated in advance and are known to all contestants, (iii) usually the teams have the same number of players participating at the same time – barring singular circumstances, e.g., penalties in ice hockey, (iv) all contestants begin at the same time or the order of play is determined by lot, (v) the winner is determined in an unambiguous fashion, usually by accumulating the most points, whatever points are called, or by crossing the finish line first, etc., not by the subjective opinions of judges who raise cards upon which is written the number of points scored, usually from one to ten, often from nine to ten, the score depending upon the subjective opinion of that judge – an opinion vulnerable to national chauvinism, point inflation, and stupidity, cf., some of the Olympic Games, the ones that, in my opinion, do not belong in the Olympics, e.g., synchronized swimming and gymnastics even, which is way out of hand, (vi) normally, the rules do not change during the playing of the game; but, if they do, the change or changes occur in a canonical manner that affects all players in the same way, (vii) the winner is not predetermined. This list of game rules may not be complete, but it is sufficient to distinguish between a proper game like gin rummy and an improper game like the stock market – or life! Life is not a sport!

[Note in proof (6-29-97). For years advertising companies have been telling terrible lies about their products. Now, Gatoradeä, the drink, does essentially what it is advertised to do. It tastes bad, but it replenishes important minerals lost during athletic activities. Nevertheless, as far as anyone can tell, the advertising company does not feel that it has done its job until it has concocted a big lie about something. Since lying about the product is inconvenient, Gatorade’s ad agency lies about life. That’s right. They spout very bad philosophy. It’s as though they cannot rest until they have done something wicked. So, they explain (painstakingly) that “Life is a sport.” This is much worse verbal garbage than the lies motor oil manufacturers tell about their motor oils.]

Definition (improper game). An improper game is a competition that is not a proper game.

Note. Some games are not competitive, despite the bad attitudes of some participants, e.g., music, mathematics, but these are not thought of as games by most players despite their insistence upon being called players.

Evils of Improper Games

If someone is forced to play an improper game, we have tyranny, a violation of the Freedom Axiom (Axiom 1), which is why I have introduced the concept of an improper game here. If one of the stakeholders does not know the game is improper, we have falsity, a violation of the Truth Axiom (Axiom 3). If all stakeholders agree, no violation occurs.

Proof of Corollary 3

Proof of Corollary 3. For a moment let us suppose that the competition for wealth and power, i.e., the Money Game were a proper game. If unequal distribution of wealth were permitted, people would compete for wealth and, if competition for wealth were congruent with their desires, they would be exercising freedom. [Note in Proof (11-3-96). Actually, the apparent advantage, relatively greater freedom, enjoyed by lovers of the Money Game may be illusory, as the Money Game creates certain constraints of its own. Notice the misery, sometimes leading to suicide, among inveterate pursuers of wealth.] Excess wealth could be used to acquire excess political power (or excess freedom!) as discussed above. Therefore, a person whose natural talents and inclinations do not result in the acquisition of wealth under the terms of the competition would have the choice of either giving up political power, which would lead to an abridgment of his freedom later on, or entering the competition for wealth on the best terms he could get, which would result in giving up freedom immediately. In either case, we have a contradiction of Axiom 1, which must have come from permitting unequal distribution of wealth. This could be remedied by equal remuneration for all activity including mental activity, but no one’s mind can be shown to be inactive so long as life persists, so we are back to equal distribution of wealth.

The Money Game as an Improper Game

It is easy to see that the Money Game is not a proper game. It is an improper game, since the rules are written down nowhere, not everyone begins with the same capital, conspiracies exist such that it is not at all clear with whom one is competing (friends become enemies, etc.), the rules are changing continuously and in a way unknown to most players, some players are willing to commit heinous crimes to gain a business advantage, nearly everyone cheats (and the term “nearly” is merely for effect), and so on.

Now, no one should be tempted to play an improper game, which would be a violation of the Truth Axiom and, normally, other moral axioms, let alone forced to play an improper game! Further, part of our early indoctrination led us to expect that we would not have to play improper games. But, consider the millions of people who devote their entire lives to an improper game. What do we think of them? Thus, the Money Game is disallowed by every reasonable moral standard. So long as it continues to be the national religion (the world religion), mankind will be mired in a moral cesspool of his own making with no chance of ennoblement. Is this to be its destiny? Someone said, “Capitalism is the worst economic system, except for all the others.” This is not funny. It’s stupid. (I shall now exercise my ingrained snobbery.) Anyone who puts up with this state of affairs, anyone who is soft, even, on capitalism, is not a lady or gentleman! (Apparently, the author is a Victorian conservative.)

Clearly, equality of wealth modulo the small differences alluded to can be achieved most readily and most efficiently by abandoning money and educating away greed. Dematerialism aspires toward a world without money or other fiduciary instruments, such as stocks, bonds, etc. Clearly, the wealth represented by the private property in a normal person’s home, even if it includes expensive computers or power tools, is not the sort of wealth whose excess constitutes the greatest danger to others. It is paper wealth represented by money (numbers in ledgers), stocks, bonds, titles, deeds, mineral rights, etc. that permits the domination of some by others.

If the love of money causes evil, money itself must be closer to the root than the love of money since it logically precedes it. Money is practically obsolete now. (While we are accounting for purchases with our credit cards, we might just as well account for individual items separately instead of in terms of money, since money is not an invariant measure of value anyway, cf., inflation.) But dematerialism is committed to gradual change; therefore, at our present level of inflation, for example, it might make sense to set everyone’s yearly income at his age in years times $1000. Thus, a parent would receive an additional yearly stipend of $2000 for a two-year-old child. A seventeen-year-old high-school student would receive $17,000 during that year. An old man of 80, who, presumably, has a greater need for money, would receive $80,000 for his 80th year.

We don’t need a first step that’s this radical. We need only begin by taking steps to prevent the accumulation of large fortunes. This might be done by enforcing existing laws. But, the important changes are the ones that take place in our minds. It’s entirely possible that the next generation of children of the rich may reject wealth utterly, going further than previous generations of rich kids who have rejected wealth theoretically only. Another possible intermediate step might be to make food, shelter, and health care free, but retain a price on clothing, household appliances and furnishings, etc. I very much like the idea of making tools free to those who actually use them, but how this is to be determined without a lot of rigmarole or the invasion of personal privacy is unclear. Perhaps, “lending libraries for tools” makes sense.

Hoarding should be discouraged by education. In fact, isn’t it clear that this should be one of the fundamental ethical goals of education? When housing is distributed fairly and money and fiduciary instruments no longer exist as repositories of hoarded wealth, the size of one’s home will provide a natural limit on the accumulation of wealth. One can fill one’s home with power tools if one wishes, but that might severely limit sleeping space. Fine jewelry, great works of art, and precious metals are another matter and might have to be handled separately; but, if no market in these objects exists, they might cease to represent wealth – except to the insane. The place for fine jewelry and great works of art is museums. The discussion of a gradual path to isopluty (equal wealth) is deferred until Chapter 12.

Corollary 4: What If Everyone Did It?

Corollary 4. If a violation of one of the other morals would result from a significant number of people performing an act that a significant number of people would be inclined to perform, then that act is immoral.

Example. It is immoral to fly a helicopter over a city for purposes of transportation. If everyone did it, although traffic would be lighter, the noise would be intolerable. (The noise is intolerable when one or two do it. This may not be the case when quiet helicopters are built, but other environmental drawbacks should be expected.)

Corollary 5 Specifically Permits Abortions and Drug Use

Corollary 5. It is immoral to interfere with an adult who wants to have an abortion or an adult who wishes to take drugs.

Comment on Corollary 5. Although Corollary 5 is self-evident to reasonable people, American society, currently, suffers from an “epidemic” of mass hysteria concerning drug use. Therefore, I shall provide an appendix to this chapter that is taken from essays that appear also in Vol. I of my collected essays [7]. Currently, most of the essays on drugs from that volume can be found at http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/debate/opinion.htm on the Internet. If the above web address is passé, try a search on “Thomas L.Wayburn”.

The reader understands that I have chosen abortion and drugs because they are each at the center of controversy so inflamed that partisans vote for policies that are not in their own interests to be on the “politically-correct” side of the debate (as they understand it), normally for reasons that have nothing to do with anything that concerns themselves personally. Thus, these issues violate Adam Smith’s principal conjecture concerning human self-interest, although Smith himself was well aware of exceptions such as these. One can imagine a rather long list of similar topics concerning which this philosophy would come to similar conclusions, and some of us will see relatively insignificant differences in perspective blossom into themes for mass hysteria [e.g., same-sex marriage (added 7-31-2004)].

Theorem 1 Establishes the Immorality of Material Compensation for Economic Deeds

Theorem 1. It is immoral to accept material reward in return for what one does, gives, or says.

Proof.

I. Violation of the freedom of others

Accepting material rewards creates materialism, which violates the Freedom Axiom, since, if one person accepts material rewards, others must do so as well to avoid having their freedom abridged by someone who accumulates excess material wealth. This might be avoided by keeping the material rewards the same for all gifts or deeds, but some people give or do nothing for which anyone wishes to compensate them, which leads to a contradiction. (Such a person might be an artist such as Van Gogh who received virtually no compensation during his life but whose paintings now sell for millions – a little late from Van Gogh’s viewpoint.)

II. Interference with one’s own freedom, which, if you remember, is inalienable

A. Compensation for extrinsically motivated activity tends to create a bias toward that activity, which diminishes freedom, in particular the opportunity to become intrinsically motivated.

B. Compensation for intrinsically motivated activity tends to undermine intrinsic motivation according to the theory of Deci and Ryan [5].

Theorem 1 Disqualifies Employment as an Institution

It is easy to see that Theorem 1 shows that employment, which, in most cases, is merely a form of prostitution or slavery, is immoral. Actually, the Ninth Amendment makes employment unconstitutional, as the right to liberty is “unalienable”; i.e., it may not be transferred. But, employment constitutes just such a transfer of liberty. Clearly, the Founding Fathers could not have forgotten the Declaration of Independence when they wrote the Ninth Amendment: The enumeration in the Constitution of certain rights shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people. This surprising result makes more sense when one puts it in historical perspective. Probably, when they referred to “the people”, the Founding Fathers had in mind small land holders and self-employed craftsmen.

The Rights of Children

The Rights of Members of Social Links

As defined above, rights are (i) freedoms that don’t violate accepted morals and (ii) entitlements that are guaranteed by accepted morals. Axiom 1 (The Freedom Axiom) protects the freedom of adults from incursions, but does not protect the freedom of children completely. If we had stated the first part of Axiom 1 in terms of individual human beings, we would have given children too many rights. Parents must be able to control their children. Indeed, by stating Axiom 1 in terms of the adult members of human social links, we established the responsibility of the adult for the behavior of the child. On the other hand, the child normally belongs to two social links, the social link of the mother and the social link of the father. These are not the same. Axiom 1 prevents one of these social links from abusing the other, but it does not prevent the child from being abused if both parents consent to the abuse. Thus, child abuse by the father would be immoral according to the Freedom Axiom because it interferes with the mother’s social link, which contains the same child – normally. Likewise, child abuse by the mother would be immoral. The mother and the father serve as a system of checks and balances. The unlikely event in which both the mother and the father conspire to abuse the child is not covered by Axiom 1. We must address this difficulty.

The Rights of Children As Individuals

Children do not enjoy the same rights as adults. Despite our philosophical love of symmetry, we must recognize at the outset that the relationship between adults and their children is not symmetric. The child may view the adult as a foreign sovereignty and the adult may view the child as a sovereign animal who has the potential to become an adult human being. The rights of children are based on morals that have been established by the antecedents of the children. The morals do not necessarily apply to the child, but they regulate the behavior of the adults who are responsible for the child’s welfare, namely, the parent(s) or guardian(s).

The responsibility of parents for children can be derived from Axiom 2 and Axiom 1. Axiom 2 requires the parents to treat the children with “every possible kindness” because as human beings children qualify as animals. On the other hand, according to Axiom 1, one is responsible for how one’s own children affect other human social links. This, in turn, will be affected profoundly by how children are treated. In addition, Axiom 1 provides guarantees for future human social links to which one’s children will eventually belong, provided only that they survive and make normal progress toward independence. Finally, Axiom 1 establishes the child’s personal sovereignty, which permits us to determine how children will be treated when they do refuse to surrender their sovereignty and are in conflict with their parents or guardians. Thus, the treatment of children falls into the category of derived morals.

Rights of Future Social Links

Children are protected under Axiom 1 from any activities that would interfere now or in the future with the freedom of the human social link whose adult member the child will become. This is the principle that permits us to derive an environmental theorem from The Freedom Axiom, if we choose not to make respect for the environment part of the second axiom (to preserve independence of the axioms). It rules out many harmful acts. It rules out interfering with the child’s education, which might affect the relative freedom of the future human social link. It rules out environmental pollution, and it rules out the incurring of other social deficits, including financial responsibilities that will fall upon posterity. Thus, modern society is very much in default with respect to these prohibitions. According to Axiom 1, children have a right to find the world in decent shape with rational institutions in place. The advanced state of decay of the world and the corruption in the institutions of human society represent a betrayal and a breach of faith with posterity. The world (society) owes young people profuse apologies and nontrivial reparations. I find it exceptionally irritating when I hear adults say to young people, “Remember, the world doesn’t owe you a living.” I beg to differ.

The Rights of Children As Animals

The future of children is protected by Axiom 1, but not everyone will agree as to what best ensures the future relative freedom of growing children. Axiom 2 (The Environmental Axiom) protects children from cruelty because Axiom 2 requires animals to be treated with “every possible kindness” and human beings are animals. (Even people who do not believe human beings are animals are probably not willing to see children treated worse than animals.) Clearly the possibilities for treating one’s own children with kindness exceed the possibilities for treating grizzly bears living in wildernesses with kindness (although we must treat the grizzly bear much better than we have treated him in the past). The possibilities for kindness to children exceed even the kindness that we lavish on pets. The morals that govern the treatment of animals, then, would apply a fortiori to the treatment of children and would immediately rule out cruelty, which is, after all, our first concern but would allow the adult to assume control over the child, which, hopefully, is in the child’s best interest. The identification of children with animals is in no wise demeaning, especially as the recognition of the nobility of the animals is becoming more widespread, and, I imagine, not many parents would dispute the claim that the identification is realistic. After all, ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, does it not? Since Axiom 2 is used, the children’s theorem, Theorem 2 below, is a derived theorem rather than a corollary of Axiom 1. Logically it should follow the statement of all of the axioms, but this is of no importance.

The Rights of Children as Sovereigns

We have already assigned sovereignty to the child. But, animals, too, are sovereign over their own beings, which certainly ought to play a role in how we treat them. Personal sovereignty sounds like it might be a very high degree of attainment, but it is no higher than the status accorded to animals; and, in particular, it is insufficiently high to protect the freedom of individuals, in the here and now, from incursions under Axiom 1. Thus, although it doesn’t sound like much, an adult social link has a status higher, according to its entitlements, than that of a sovereign lord. Even before a child is aware of his (or her) sovereignty, though, that sovereignty must be protected by adults, including adults in the same social link. I do not know from personal experience, but I dare say that many parents have felt as though they were raising a little king or queen based on the demands placed upon them.

The personal sovereignty of children determines how they may be treated by adults from their own social links when they are in conflict with them. This conflict resembles war in many respects, and, if parents are at all in possession of their faculties, wars with children should be brief and normally should end with the adult(s) victorious. The child may be treated no worse than one would treat a captured monarch after his defeat. (It is an interesting feature of dematerialism that wars between children and their parents or guardians constitute the only category of wars the probability for which is not reduced essentially to zero.)

Child Development