Chapter 1. Toward a Rational Social Contract

But the social order is a sacred right which serves as a basis for all other rights. And as it is not a natural right, it must be one founded on covenants. – Rousseau, The Social Contract

Governments cannot really divest themselves of religion, or even of dogma. ... Governments must proceed on dogmatic assumptions, whether they call them dogmas or not; and they must clearly be assumptions common enough to stamp those who reject them as eccentrics and lunatics. And the greater and more heterogeneous the population the commoner the assumptions must be. ... I repeat, government is impossible without a religion: that is, without a body of common assumptions. – G. B. Shaw, “Preface to Androcles and the Lion”

Table of Contents

The Constitution Is Unacceptable Because of Our Desperate Need for Autonomy (Freedom)

Our Constitution Is Unacceptable Because of Its Inconsistencies Due to Fundamental Religious Content

Separation of Church and State

Separation of Church and State Fails

Argument 1. The Rule of Precedence

Argument 2. The Religious Nature of the Bill of Rights

Argument 3. Our Need To Espouse Religious Values

Other Reasons Why the Current Social Contract Is Irrational and Perforce Invalid

Government Propaganda and Gratuitous Private Propaganda

Superstition and Old Wives Tales

Community and a New Type of Social Contract Based on Rational Morals

Taboo Morality Is Coincident with Hypocrisy

Rational Morals Are Easy To Satisfy

Absolute Morals Approachable But Unattainable

The Basis for Moral Axioms and Philosophical Assumptions

We Are Not Yet in a Position To Live without Laws

Laws and Morals Should Be but Are Not Consistent

Rational Morals Provide the Nucleus of a Set of Common Assumptions in a Rational Society

Occurrence Implication and Occurrence Equivalence

Occurrence Equivalence as Evidence of Divinity

A Minimal Proper Religion As a Social Contract

Building Upon a Minimal Proper Religion

A Rational Philosophical Basis for a Minimal Proper Religion

The Subject of The Varieties of Religious Experience Compared to a Proper Religion

How a Social Contract Based on Consensus Might Work

Becoming a Party to a Valid Social Contract

Definitions of Terms Employed in Fundamental Theorem

Sustainable Happiness for All of Humanity

2. Happiness in the Colloquial Sense

1. A Stable (Human) Population

2. Adequate High-Grade Renewable (Sustainable) Energy

3. Sufficiency of One Kilowatt Per Capita Renewable Emergy

Universal Sustainable Happiness

Negotiable and Non-Negotiable Fame and Influence

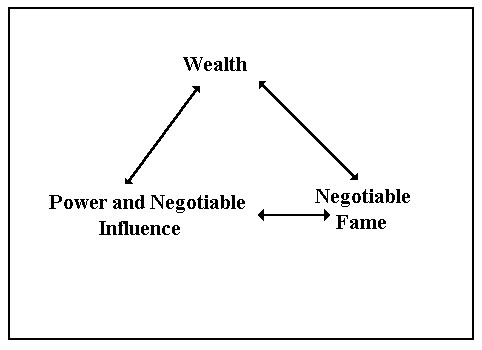

Occurrence Equivalence of Wealth, Power Including Negotiable Influence, and Negotiable Fame As S*

The Fundamental Theorems and Premise

Abstract Happiness vs. the Elimination of Misery

Preconditions for Happiness as Defined by Me, Not Popper, Who Doesn’t Bother To Define

Miseries that Popper Believes Should Be Addressed

Is There a Utopian Capitalist Religion?

Appendix B. The Definition of the Ruling Class

On Government

The Social Contract

Introduction

Definition (Social Contract). A social contract is a covenant between (1) governments and the governed, (2) between institutions and individuals, (3) between institutions, and (4) between individuals. It amounts to an agreement with general applicability commonly understood to regulate the behavior of every member of society just as a legal contract regulates the behavior of the parties who have entered into it with respect to the specific applicability of the contract – except that a social contract has much wider applicability than a legal contract.

As discussed above, we wish to abandon the institution of government, which no one likes anyway. This cannot be done without a period of delegislation during which laws must be replaced by rational morals gradually. The system of morals that we choose will determine the social contract we end up with. We expect that people who enter voluntarily into a social contract with their neighbors will behave at least as well as people who are constrained by laws normally not of their own choosing. They could hardly behave worse.

In the absence of government, Item 1 in the definition of a social contract will be discarded. This is the portion of a social contract that is supposed to be taken care of by a constitution – even though numerous exceptions are found in every case. Certain portions of the agreement between the rulers and the ruled fall under the purview of tradition, brute force, etc. The people make do as well as they can from their position of relative weakness. They hope that the tyranny under which they live will not be inordinately cruel and that constitutional provisions will not be violated excessively. To eliminate tyranny altogether it seems that government must be eliminated, in which case no constitution is needed.

Regardless of whether or not the contract that governs the behavior of institutions and individuals be written down or not, its provisions must be crystal clear and well-understood and accepted by everyone – or nearly everyone. In a well-ordered society with no government, the social contract must be the basis of the behavior of all those who accept it. They must internalize the morals embedded in the social contract in such a way that their behavior is, for all practical purposes, voluntary. The members of the community are free people who do what they do because they want to. In this chapter, I shall discuss the social contract I would like to have after I explain why I wish to reject the social contract that we actually do have.

Our Current Social Contract

Our current social contract, while centered upon the Constitution, is composed of many disjoint elements some of which are not recognized generally nor are they rational or just. The result is social strife and alienation bordering on outright rebellion especially among youths. The elements of what passes for a social contract nowadays require some discussion:

The Constitution Itself

The Constitution Is Unacceptable Because of Our Desperate Need for Autonomy (Freedom)

The Constitution creates numerous institutions, namely, the presidency, Congress, a judiciary, etc., whose function is to exercise power over individuals. But, individual autonomy is a prerequisite for happiness in the sense of Deci and Ryan [1]. Thus, despite the so-called checks and balances and a sort of fictional responsibility of these institutions to serve the people, we have become victims of the most insidious tyranny imaginable, a tyranny of which many people are unaware. Why should people rebel against tyranny if they have been convinced that they are free? We wish to make clear in this essay the importance of rejecting presidents, members of legislatures, and judges. If we wish to enjoy autonomy, necessary for happiness, we must establish a social contract that prevents the existence of all such leaders. This entails sweeping reform.

The problem of determining how social reform on an extremely broad scale shall be effected is exacerbated by the necessity to achieve widespread social reform essentially without so-called leadership! Normally, what is euphemistically called “leadership” is an impostor term, in the sense of Bentham [2], and should be called tyranny. Tyranny will not resolve mankind’s most serious problem, its greatest challenge, and, perforce, its most dramatic opportunity for universal ennoblement, namely, the elimination of enormous differences in economic well-being and the creation of communities of people who share real wealth virtually equally with essentially no government or “leadership” whatever! Each (undiminished) person must be his or her own leader. This will be discussed in greater detail in later chapters especially Chapter 6. [Having said this, no one should be surprised when I refuse to join with any people for any purpose – even people who agree with me who have organized to implement my ideas. Following William Morris, I reject all political parties, activist organizations however well intentioned, all and any organizations of every stamp. Don’t you see that these are ideal breeding grounds for “natural leaders”. If the government is to be overthrown, it must be overthrown by individuals working alone and anonymously.]

Our Constitution Is Unacceptable Because of Its Inconsistencies Due to Fundamental Religious Content

Religion and Philosophy

Definition (Religion) [from Random House Dictionary [3] (RHD)]. 1. a set of beliefs concerning the cause, nature, and purpose of the universe, esp. when considered as the creation of a superhuman agency or agencies, usually involving devotional and ritual observances and often having a moral code for the conduct of human affairs. [italics mine], 2. a specific and institutionalized set of beliefs and practices generally agreed upon by a number of persons or sects: the Christian religion; the Buddhist religion. 3., 4., etc., not relevant. Clearly, the “beliefs and practices” referred to in Definition 2 might have moral implications.

Definition (Philosophy) [from RHD [3]]. 1. the rational investigation of the truths of being, knowledge, or conduct. 2. a system of philosophical doctrine: the philosophy of Spinoza. 3. the critical study of the basic principles and concepts of a particular branch of knowledge: the philosophy of science. 4. a system of principles for guidance in practical affairs: a philosophy of life.

According to the RHD, then, philosophy and religion have much in common as well as a number of differences depending, of course, on which sense of either word is intended. We may regulate our affairs, then, according to philosophical principles if we accept Definition 4 of philosophy and reject the Moral Code Clause in Definition 1 of religion. Unfortunately, we cannot prevent people from recognizing that the italicized portion of Definition 1 of religion and Definition 4 of philosophy are nearly equivalent. We have fallen into a trap by trying to invoke a principle that can be construed to be religious in nature by anyone who wishes to so regard it. Indeed, in our zeal to avoid the establishment of religion, we have committed the very sin we deplore.

Now, as far as I can tell, religionists – even the most unreasonable right-wing Christian fundamentalists – are not trying to incorporate their cosmological and hermeneutical beliefs or their rituals (other than prayer) into the law of the land. Invariably what they are after is to have their moral code for the conduct of human affairs enacted into law. Therefore, the moral aspect of religion is what should interest us. While it is true that many people believe, with good enough justification, that a moral code alone does not make a religion, one cannot a priori rule out the possibility that many people, including, perhaps, judges and juries in courts of law, do aver that all moral judgments are religious in nature, therefore we must make allowances in advance for such a ruling. Also, consider the point of view of G. B. Shaw quoted in the epigraph.

Improper and Proper Religions

My first inclination is to dismiss all religions as improper; but that will not do. In the first place the theory of morals that I propound in this essay is, in a certain sense, a religion. I claim it is a proper religion, that is, it is not an improper religion. Improper religions are easy to identify. I shall list a few of their characteristics, which should suffice to disqualify all of the religions that threaten the world currently. A religion shall be said to be an improper religion if it has one or more of the following characteristics or if it is inconsistent:

1. It claims to be absolutely true – for all time – never in need of revision. Although most improper religions have undergone considerable revision, they are always in a state of reaction to enlightenment. They lose one position after another to science, but they adjust and continue to assert absolute validity. [Bertrand Russell]

2. It claims to be the sole correct religion and nonbelievers are placed in an inferior position to believers. If the claim is that nonbelievers are in some sense doomed, this constitutes fraud as well as child abuse. [Note in proof (5-30-98). It is generally agreed that free speech does not extend to yelling “Fire” in a crowded theatre. Then, a fortiori, yelling “Eternal damnation” should not be protected either.]

3. It relies on circular reasoning, e.g., such and such doctrine (A) is written in the Holy Bible from which one may deduce that (B) the Holy Bible is the inerrant word of God, therefore the doctrine (A) is true. That is, if A, which was assumed, then B and if B then A, which was to be shown. Regrettably, to prove A, A was assumed to be true at the outset. (I do not know where in the Bible we are told that the Bible is the inerrant word of God. Nor, can I show an example of circular reasoning in connection with the Bible. I do not need a case of circular reasoning to show that Christianity, as it is actually practiced, is improper!) The point, though, is that any religion that is based in whole or in part upon reasoning of the type: if A then B, if B then C, ..., if Y then Z, and if Z then A, i.e., circular reasoning, is an improper religion.

4. It comes with an excessive amount of intellectual baggage that must be taken on faith. It makes claims that cannot be substantiated by observation or experiment, which it justifies by unfalsifiable statements. It claims to know what no one can know – in particular the nature of God. Often it incorporates some sort of belief in magic.

5. It attempts to increase the number of adherents by unethical means such as childbirth or outright lies – frequently preying on human weakness.

6. It has a priesthood that claims to be invested with special knowledge sometimes received directly from God and, therefore, not open to debate.

7. Normally, it incorporates some form of irrational taboo morality.

8. Typically, it will shun all debate with nonbelievers even though it will claim not to.

9. Frequently, money is involved in one way or another.

10. Usually, its code of ethics will accommodate evildoers if they subscribe to its church.

Proper religions have none of these characteristics. I believe a simple heuristic may be employed fairly safely; namely, if it has a church, it’s most likely improper. Please remember that, if a religion be inconsistent or have even one of the above characteristics, it is improper by definition. Certainly, I do not imagine that I have some distinctive right to disqualify improper religions from consideration in a social contract without a general consensus of my neighbors, by which I might have to consider everyone in the world in some cases.

Separation of Church and State

Presumably, the Founding Fathers of the fledgling independent nation known as the United States of America envisioned a State in which every man is free to worship whatever hypothetical deity he wishes in the manner he wishes provided the mode of worship or the rites of his religion do not jeopardize the compelling interests of the State. Probably, though, (it must be admitted) they did not intend to protect people who wished to reject all of religion including every Christian sect.

In May, 1989, in my essay “The Separation of the State from the Christian Church” [4] (renamed “The Separation of the State from the Christian Church and the Case Against Christianity” [5]), I tried to make a case for the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. I hoped to show that religionists may not incorporate their arbitrary moral judgments into the law of the land. [In this essay, quotes from my earlier papers will be distinguished by wide margins.] In 1989, I wrote as follows:

The First Amendment of the Constitution guarantees, among other things, that “Congress shall make no law respecting [regarding, concerning, with respect to] an establishment of religion ...” This, together with the expressed belief of the founding fathers, has provided the foundation of what has come to be known as The Doctrine of Separation of Church and State. This doctrine has been interpreted to mean that the public affairs of the people of the United States shall not be imposed upon by the particular beliefs of any religion no matter how widespread its acceptance. Even if the Doctrine were not supported by the Constitution, we would have to respect it because without separation of church and state there would be no possibility of peaceful coexistence of separate religions, cultures, or lifestyles within the United States. The Doctrine means much more than toleration of various religions; it means that individuals must be spared any impingement on their lives by any religious beliefs whatsoever, if that is what they desire. Adherence to religious belief has been shown to be entirely superfluous to the socialization (rendering fit for human companionship) of humanity, so there is no reason why people should be subjected to it against their will.

The point is that the position (stated above) that I took in my 1989 essay could be defeated by a clever debater who would argue that our laws already contain numerous moral judgments, which are never construed to be laws respecting an establishment of religion, therefore the Establishment Clause is either null and void or must be construed in a manner unfavorable to my 1989 argument. And, finally, laws prohibiting abortion and mandating prayer in school are not, after all, unconstitutional, since we have a law, for example, against murder, which is obviously a moral decision, perhaps derived directly from the Sixth Commandment.

Separation of Church and State Fails

Regrettably, the principle of separation of church and state cannot be justified completely on the basis of the First Amendment. This prevents the Constitution – in particular the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment – from protecting us from right-wing fundamentalists who wish to enslave us by solidifying the totalitarian theocratic nature of the State and by introducing into the law of the land the irrational restrictions placed upon our freedom by their improper religions. The arguments that undermine the Constitution are three in number. Generally, these arguments are not considered by champions of so-called separation of church and state, particularly Atheists and Secular Humanists.

Argument 1. The Rule of Precedence

Suppose a religionist school board decided to teach celibacy in the public schools. The religionist would argue that we already teach that killing other people is wrong, which is a moral judgment taken directly from the Bible; therefore, since celibacy is mandated by the Bible as well, it is valid to teach it in the public schools, according to the “rule of precedence”. Teaching celibacy in the public schools is wrong because celibacy is a personal or taboo moral and we have argued that no consensus can be reached regarding personal morals, but the First Amendment is no help because of the precedent provided by “Thou shalt not kill”. We need a new way to defend ourselves from the imposition of irrational or arbitrary morals upon us or upon our children by religious bigots. Sexual inhibition is extremely harmful according to many thinkers, including Wilhelm Reich [6], Bertrand Russell [7], and myself [8]. Thus, we must continue to look for a social contract we can live with.

Argument 2. The Religious Nature of the Bill of Rights

In addition to these inconsistencies, the Bill of Rights, itself, is inconsistent. Although not precisely “made” by Congress in the same sense that Congress makes ordinary laws, the Bill of Rights was originated by Congress and the spirit of the Establishment Clause was broken simultaneously with its creation because of the numerous moral judgments in the Bill of Rights, e.g., no cruel or unusual punishment, etc. If the Founding Fathers intended to disparage making laws respecting an establishment of religion, they should have recognized the inconsistency of a constitutional amendment respecting an establishment of religion. This argument was suggested by the poet Emily Nghiem.

While those who claim that the founding of the United States was based on Christian values are not entirely wrong, it is not clear that the common set of Judeo-Christian values upon which our country was based is useful or desirable now. What is clear is that the society based upon these values is coming apart at the seams and is on the brink of collapse.

What is worse, the Constitution fails to preclude the passing of laws based upon irrational morals; it leaves nearly every moral imperative untreated; and it is woefully vague with respect to the morals it does not neglect altogether. The result is that, in the United States, at the present time, we have widespread disagreement concerning the question of which morals are valid and which are not. It is fair to say that we are on the brink of another civil war. The worst possible catastrophe on the horizon is not the possibility of civil war, but the possibility that the wrong side might win.

Nevertheless, although the Founding Fathers probably did not have freedom from religion in mind when the First Amendment was enacted, the wording is sufficiently clear that religionists who claim that it does not imply separation of church and state and that they may lobby to have anti-abortion legislation enacted are not entirely honest. I continue to be appalled at the unfair use of media by televangelists to promulgate a religion that, if it were at all valid or beneficent, could be encouraged by honest means.

Recognizing the religious character of the Constitution, and perforce its inconsistency, has an interesting side effect; namely, it removes a certain weakness in the liberal position generally opposed to right-wing fundamentalists with which I have not been entirely comfortable. I have noticed, in particular, that conservatives who espouse obsolete and pernicious doctrines frequently are able to score points at the expense of the more nearly correct liberals because liberals are not willing to take a position radical enough to make sense. (Radical means “getting to the root of”.) They are well-intentioned, but they still spout nonsense, which makes them easy targets for right-wing critics. For example, laws prohibiting abortion might be attacked by citing the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment; however, the sovereignty of women over their own bodies is also a religious position; and, particularly, if it is accompanied by advocacy of drug prohibition, it is completely irrational. Also, liberals tend to accept the work ethic, which has religious origins (in Genesis); but jobs are out of the question for a large segment of the population, which is entirely justified in its reliance on crime – given the circumstances under which work is available if, indeed, such circumstances even exist.

Argument 3. Our Need To Espouse Religious Values

I consider a moral code sufficient but not necessary for a religion. Thus, I can’t disparage religion or isolate religion from public policy since almost all public policy (except for minor procedural matters, e.g., dates of public assembly) has moral implications. At least, I challenge the reader to suggest a public policy to which I am unable to assign moral implications. Perhaps not all moral rules for human conduct should be considered religious in nature, but I consider them religious in nature, which I may do if I wish.

The solution to the problem of facing the tragedy that religion, at least the all-important moral aspect of religion, may not be separated from public policy is presented in this chapter. Clearly, it is the rule-giving aspect of religion that gives rise to divisiveness nowadays. Thus, we are forced to consider any moral system whatever – a religion. Probably, a common core set of religious values is necessary to bind a group of people into a community. In the absence of a constitution, I must show how to arrive at a new social contract upon which nearly everyone can agree and which can supplant the State, government as we have grown to know it and hate it, and, indeed, leadership as it normally manifests itself. To achieve consensus through a common religious morality, I must find a way to exclude the dogma associated with the Judeo-Christian tradition and other religious traditions. Upon such dogma we can never agree.

The probability of achieving a general consensus on irrational morals is practically nil inasmuch as one set of irrational morals is no more attractive than another; therefore, the probability that people of diverse cultural, racial, and religious backgrounds should choose the same set is close to zero. A route to consensus is, indeed, what we seek; and it stands to reason that the fewer items that we require general – practically universal – agreement upon, the greater the chance of reaching consensus.

Other Reasons Why the Current Social Contract Is Irrational and Perforce Invalid

Every human being finds himself (or herself) at the beginning of his life in a strange world, presumably without having requested to be sent there. It can be argued that each person has a right to find the world in perfect shape with an ideal social system in place, not having had the opportunity to select the world he would like or the system he would choose and not having been here to arrange matters for himself. From the viewpoint of the previous generations, it doesn’t make sense to deny that the world owes the newcomer a living. The world (society) owes the newcomer much more, in particular profuse apologies for the state of the world that the newcomer finds and nontrivial reparations for not fixing it before the newcomer’s arrival. It is the business of this essay to prove that society is irrational, to describe what a rational society would be like, and to prove that such a society is feasible. If that be true, every normal (undiminished) adult is to blame that society is still not rational.

Clearly, each newcomer will not have signed the Constitution, ratified the laws of the land, or agreed upon the established institutions, but he has a right (or it can be deduced that he has a right) to find them at least reasonable, which they are not. This is what needs to be remedied. Until it is remedied, dissidents may not be treated as criminals. According to the logic just presented, all of the inmates of our jails are political prisoners. No one knows what their lives might have been like in a reasonable world.

Indoctrination in the Schools

Our early and sometimes later schooling consisted of indoctrination that amounted virtually to promises that can never be kept. This was done according to someone’s intentions. We were taught conventional falsehood, which many of us still understand as sacred truth, e.g., the greatness of our nation, the guarantees associated with hard work and conformity, etc. The way we were introduced to particular key words by our parents during the dark ages of our minds (before the age of reason) has clouded our subsequent thinking. It can safely be said that practically no one sees the world as it actually is.

Government Propaganda and Gratuitous Private Propaganda

As O’Flaherty says, “If there was twenty ways of telling the truth and only one way of telling a lie, the Government would find it out. It’s in the nature of governments to tell lies.” [George Bernard Shaw, O’Flaherty, V. C.] The government must tell lies because tyranny cannot be maintained without the consent of the victims, who will not give their consent unless they can be convinced that they are better off than they really are. The corporate media know that they must corroborate the party line to satisfy their sponsors, some of whom own the country and the government as well – for all practical purposes. The large corporations, which either own the country or are owned and/or controlled by those who do, know what to say. This is adequately documented in this essay and more thoroughly in the book by Herman and Chomsky [9]. This party line perforce becomes part and parcel of the social contract as the parties to the contract have accepted it and have been promised that it is true, in return for which they sacrifice their lives or the time of their lives. All of the conditions of a contract are met.

Tradition

The

glorification of wealth and excessive consumption has been inculcated by

A De Facto Caste System

If we are truly equal and live in an equal opportunity egalitarian society, why do we make a distinction between exempt workers and non-exempt workers? See Chapter 6 for additional discussion of the caste system in America, an aspect of our culture that is rarely mentioned in the President’s State of the Union address.

Brute Force

The element of brute force in our de facto social contract is exercised through cops and courts and brought home otherwise by the necessity to be employed or to desire to be employed.

Our National Religion

Our national religion is the Judeo-Christian tradition of teaching blind obedience to the false gods of money, power, and fame. Clearly, this is an element in our social contract.

Superstition and Old Wives Tales

As an exercise, the reader may list a few examples of superstitions and old wives tales that qualify as elements of our social contract.

Community and a New Type of Social Contract Based on Rational Morals

Community Replaces the State

The exhaustion of our readily available supplies of high-grade energy will make large sovereign entities impossible to govern within the foreseeable future. The conclusions of Chapter 2 should convince us that large sovereign states like the U.S. are doomed. We need small lightly linked communities such that everything we need is within walking distance. The exigencies of economics will require that these communities be nearly self-sufficient. Again, see Chapter 2.

The members of these communities will be sufficiently few in number that an agreement upon a new social contract based on very few rational moral axioms and a small number of additional (rational) assumptions is not absolutely out of the question. We must find something of this sort that we can agree upon. We must have consensus to dispense with government and the concomitant strife arising from conflict between the rulers and the ruled. We cannot have a constitutional democracy, but we can exclude irrational religious principles and base our community upon a religion, a minimal proper religion, that makes sense and is easy to follow. We can get rid of tyranny if we replace laws by rational morals. This new type of social contract, based on a minimal number of conditions accepted by nearly everyone, is the binding force within the community and the only hope for sustainable happiness.

Definition (Minimal Proper Religion (MPR)). A minimal proper religion (MPR) is a proper religion that incorporates the minimal number of behavioral requirements necessary to ensure “sustainable happiness” for all of humanity. An MPR places constraints upon those who agree to follow it, but only those constraints upon behavior and public policy that cannot be relaxed without creating unbearable misery for a significant portion of humanity.

On Morals

Most of the material presented below in wide-margin format has been taken from an earlier essay on drug policy [10]. A few passages differ from the original rendering.

Rational vs Taboo Morality

I choose to distinguish two categories of morals: The first category consists of personal or arbitrary morals, the violation of which does not interfere with the freedom or well-being of any other person except, perhaps, in an irrational way. Thus, we could call these morals irrational morals without stretching a point. For example, the homosexual activities of a young man may distress his mother but only because of her irrational bias. Her freedom may be limited because she is afraid to face her friends; but, again, this is due to her misunderstanding of the situation. What I mean by [i] arbitrary morals [or [ii] irrational morals] is roughly congruent with what Bertrand Russell [7] calls [iii] taboo morality. [Let us take these three terms [i, ii, and, iii] to be synonymous for our purposes.] For the most part, arbitrary morals consist of proscriptions of certain activities that are disallowed by primitive cultures for non-rational reasons or to advance the unspoken agendas of the ruling or priestly classes, which might correspond with the best interests of the people from time to time but in an unsystematic way. Examples from this category are the requirement to do no work on the Sabbath, the proscription of eating meat on Friday (no longer in fashion), the prohibition of certain sexual acts, and the use of or abstinence from the interesting drugs.

For example, doing no work one day of the week may be a good idea to permit individuals to [refocus] themselves spiritually and to reconsider what they are doing on the other six days. Also, it might make the tribe more cohesive and facilitate social activities to make Sunday the day off for everyone, but we no longer live in sufficiently small tribes that the regimentation of requiring the day of rest to be the same for everyone can be justified. Even the seven-day cycle is unsuitable for many people whose inclinations and needs differ from the norm. [Soon, we may be living in eco-communities that will resemble tribes more than they resemble nations, but I hope we shall be able to tolerate great diversity within these “tribes”.]

[Note in proof (7-10-04). Perhaps our mean solar days (or sidereal days), lunar months, and sidereal years should be put on the decimal system. Days (either mean-solar or sidereal, whichever is best) could be divided into decidays (144 minutes), centidays (14.4 minutes), millidays (1.44 minutes), and microdays (0.0864 seconds corresponding to greater precision in the measurement of time). (My watch shows hundredths of seconds!) The mismatches between days, months, and years could be dealt with in a number of ways. I believe the day is most important and we should count up to a thousand days before beginning over. We might then write the day of the thousand-day cycle, followed by the month number until 33863 months or one million days have expired, after which we might re-initialize the month number. The number of sidereal years that will have passed is about 2,738, after which time someone else can figure out what to do. Dates might look like this 512,846:21,319:1408, the 846th day of the 512th thousand-day cycle, the 21,319th month, and the 1408th year of our era, the First Era. Dates before the initiation of this system could be written 7-10-2004, for example. This idea just occurred to me and I have given it about ten minute’s thought only. I don’t think I am quite the right person to work out the details. But, notice that, by including three decimal places, I can identify to the nearest minute Moonrise on the night of the Full Moon of the Autumnal Equinox. For example, 512,846.743:21,319.500:1408.750 would represent Moonrise of the Harvest Moon if 0.743 were the time of Moonrise and the 512,846 were the number of the day and 21, 319 were the number of the month of the Autumnal Equinox in the 1408th year.

The second category consists of higher morals the violation of which does interfere with the freedom and well-being of others, which might include plants and animals, although harming plants and animals always impacts on the human race as well. Examples from this category are “Thou shalt not kill”, “Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor”, thou shalt not incinerate trash, especially in the middle of an urban neighborhood, thou shalt not impose thy religious beliefs on others, thou shalt not start forest fires wantonly. These higher morals correspond to what Bertrand Russell calls rational morals, although they might be based on aesthetics as well as reason and utility. We shall reject lower morals as a criterion for law.

Shockingly, since the social contract – upon which we wish to achieve nearly universal consensus – can be construed to be a religion according to the RHD, I shall be advocating a community religion. But, most religions are harmful, as shown abundantly in my essays on religion. My solution to this problem employs the concept of a minimal proper religion, which, in turn, depends upon our ability to distinguish between proper and improper religions as defined previously.

Taboo Morality Is Coincident with Hypocrisy

Now, an important point made by Russell in his essay “On Chinese Morals” [7] is that, in many cases, taboo morals, particularly sexual morals, are morals that “we preach but seldom practice”. We set up requirements that no man of spirit can live by. We are not supposed to lust after a beautiful, sexual, and otherwise attractive woman; and, as soon as we do, which we cannot seem to help, we are wracked by feelings of guilt. Moreover, we hold our elected officials to higher sexual standards than we ourselves (I am speaking of men in particular now) could ever uphold were we faced with temptations that a young, handsome millionaire who reeks of power is subjected to nearly daily. This leads to gross hypocrisy of the most egregious type, as it discourages talented people from becoming candidates for positions that will be exposed to moral scrutiny. (I find it difficult to imagine that anyone could hold such a position for an appreciable length of time without suffering moral decay – as Lord Acton’s proverb would have it.)

Rational Morals Are Easy To Satisfy

Russell points out that the Chinese don’t bother with morals that no one can live by. On the other hand, everyone is expected not to violate the morals they have adopted. The Chinese take their morals very seriously! Of course, Judeo-Christian morality is full of ridiculous morals and neglects some very important ones. Since Judeo-Christian morality does not satisfy reasonableness, aesthetics, or utility, it should be rejected. To put it bluntly, it’s wrong! Instead, why not select rational morals that we can actually live by, thus avoiding all the hypocrisy, guilt, and stupidity – the stories of which fill our junk periodicals and even first-class newspapers! Regrettably, many of our laws are based on the Jewish and Christian religions concerning which we shall elaborate in a moment. That’s part of the problem. Let people have sex with whomever and under whatever circumstances they wish and, for God’s sake, get high whenever they wish and, in particular, whenever it’s the appropriate thing to do. Every drug in its time and a time for every drug. We are human. Let us act like human beings – and enjoy our natural atavistic animal natures too. It is easy to be virtuous. Unfortunately, we Westerners haven’t the foggiest idea of what virtue is. Russell has had the plain common sense to transcend this difficulty; and, by standing on Russell’s shoulders, I have illuminated the subject further.

Morals Are Preferable to Laws

The sense in which I use the word culture here is distinct from fine art but rather refers to the everyday life in a community, race, nation, or similarly identifiable group of people. One could make a pretty good case that this is the only morality that matters, since practically no one adheres to secular or ecclesiastical law if he finds it inconvenient. I will argue that The Law is practically innocuous and that the reason people take only one newspaper from the box into which one drops a quarter or more to open the hatch is that not taking more than one paper is part of their culture. Cultural values discourage suicide by driving one’s car at full speed into the left-hand lane of a two-lane country road. It simply is not done! I find it amusing, and slightly disturbing, that nearly everyone ignores the Big Time morals like “Thou shalt not steal”. Nevertheless, if a particular mode of theft, e.g., newspaper theft, is not condoned by our culture, it is avoided nearly universally. Could it be that we are not particularly imaginative or creative? Clearly, laws are absolutely the last resort. They are the worst possible solution to the problem of human behavior.

The vast

litany of law ensures that ignorance of the law is part of the mind set of

every single individual – even Supreme Court justices. Does anyone else

find it strange that the country is 200 years old and we don’t even know what

the laws should be? When they raised the drinking age in

Absolute Morals Approachable But Unattainable

We would like to have a system of absolute morals, morals that are independent of culture or point of view. Of course, some religious people believe that we already have a system of absolute morals given, for example, by the Bible, but most of these people are not aware of the epistemological difficulties that would have to be overcome to establish such a system. Actually, it is easy to show that the Bible is entirely inadequate as a handbook of morals. It is inconsistent and is filled with moral advice that does not satisfy aesthetics, reasonableness, or utility.

Note. I have shown this in some detail in the essay “Separation of the State from the Christian Church and the Case Against Christianity” [5], which can be found in Vol. II of my collected essays [8], which I have called Ancillary Essays on my home page. I return to the quoted passage.

The Basis for Moral Axioms and Philosophical Assumptions

To avoid infinite recursion we need a priori principles according to which we can evaluate the basis of our system of morals. Suppose, following William James [11], we choose reasonableness, aesthetics, and utility. [Note. Reasonableness and aesthetics might be the “left brained” and “right brained” aspects of the same thing. This is to be taken metaphorically until it is shown that reasonableness and aesthetics actually reside in the left and right sides of the brain, respectively. For now, we shall write “left-brained” and “right-brained” in quotation marks.] Then we are confronted with showing that reasonableness, aesthetics, and utility are suitable metaphysical values. Somewhere we must terminate the process and agree that something must be taken on faith. Thus, in all things, even in science, faith plays a pivotal role.

Our system of morals should be derived from a complete, self-consistent, mutually independent set of first principles that can be explained to a six-year-old and upon which most educated people can agree. It is unlikely, though, that mutual independence is possible or necessary. At this writing I do not know if it is possible to derive all morality from a single principle like the Freedom Axiom proposed in this essay. (We will show that the Environmental Axiom (A2) can be derived from the Freedom Axiom (A1), but the Truth Axiom seems to be logically independent of A1 and A2.)

If, in addition, we can prove that the principles upon which our system of morals is based are optimal in the sense that they maximize personal liberty, prosperity consistent with permanence, happiness, and spiritual growth, prevent inequality and injustice, and can never lead to undesirable consequences; and, if we can find a way to win over dissent by examples and counterexamples, i.e., by inductive reasoning (not coercion), we shall have done very well indeed. A system of morals may fall short of optimality and still be good enough to gain universal acceptance within a nation whose members are finite in number. The probability of our system achieving global acceptance might depend on its success wherever it is first applied.

We Are Not Yet in a Position To Live without Laws

It will be some time before the people of the United States reach a consensus on a new social contract. In the meantime, I don’t see how we can dispense with laws immediately as much as I would like to do so. We shall have to limp along with our botched Constitution. Perhaps the most antagonistic members of society, namely, the absolutist religionists, can possess themselves with patience to a somewhat more creditable degree while we undergo what is bound to be a profound spiritual transformation. Perhaps, then, they may begin to understand what their religions are all about.

Laws and Morals Should Be but Are Not Consistent

To continue the above quote from my own essay [10]:

Whether a self-consistent and complete system of morals can be constructed or not, a subset of a system of morals or a superstructure built upon it has been chosen to be the law of the land, or at least that part of the law that deals with human and institutional behavior, as opposed to political formalities, e.g., when Congress shall meet. I submit that the law should be congruent with our system of morals and easily derivable from it. We are far from that advanced state of affairs where legislators would be unnecessary inasmuch as any normal person could determine quickly whether a given proposition was a “law” (or not) by deriving it (or its contradiction) from fundamental axioms or first principles.

In the United States, laws are not congruent with community moral standards. This amounts to a contradiction to the detriment of Law. Rather than having been derived from first principles, laws have been enacted willy-nilly to consolidate the power of the ruling class and to appease the superstitions of the people. (The ruling class is defined in the appendix of this chapter.) The American legal system is in such shambles that we can hardly be considered a society governed by laws at all. However, everyone knows that Law has very little effect on the actual behavior of people. Law is more or less the last resort. People are inclined to obey the laws they wish to obey and to disregard the rest. Presumably, however, we shall have to put up with the institution of Law for a little while longer, and the best we can do is to bring it into line with rational morals insofar as it lies within our power to do so. Moreover, we must do our best to make community moral standards more rational.

Until delegislation is complete such laws as we require should be derived from and be congruent with a system of morals upon which we can all agree. Probably the Freedom Axiom of this essay was the prehistoric basis for all laws, i.e., the necessity to give each person his share or his space. In any case, there is no possibility of a nation living in America in peace unless we can agree to embrace higher morals and to recognize that some morals are a matter of personal preference. (Even if they were the personal preference of every person in the United States, they would still be personal morals.) [I believe that the reason we have so many gray areas in our public discussions of morals is that we are talking about the wrong morals. With the system described in Chapter 3 most (better yet, all) of the gray areas should disappear.] [This ends the quoted passages from Reference 10.]

It is easy to show that morals and laws (other than procedural laws, e.g., on what day a public servant retires to private life) should be congruent.

Lemma: In any rational social contract, laws (other than procedural laws) must be identical with morals.

Proof: Suppose not. Either The Law is evil (something illegal but not immoral) or incomplete (something immoral but not illegal) or both. To elaborate:

Suppose we had a law prohibiting an act that harms no one and is not offensive to the good taste or finely honed reasonableness of a rational person, e.g., the law against adding butter in which marijuana has been sautéed to coffee. Paraphrasing Bertrand Russell: To appeal to The Law to invalidate an act that otherwise would be good is to impute evil to The Law. Conversely, if The Law did not prohibit telemarketers from calling us on our own phones (for which we pay the basic bill including line charges) whenever they chose (which it does not), The Law is incomplete. If The Law of the Land achieves anything at all worth achieving, it certainly does not achieve all that its champions would like to claim for it, namely, protecting citizens from evil.

Rational Morals Provide the Nucleus of a Set of Common Assumptions in a Rational Society

Due to the technological changes in communication and for other reasons, cultural changes occur amazingly fast these days and no one can predict what might happen if a different set of core religious values were presented to society. I intend to present an alternative core set of religious values based not on myths and superstition but rather on firm philosophical principles that satisfy our three criteria, namely, reasonableness, aesthetics, and utility. These criteria are innate, experiential, subjective, or intuitive.

Hopefully, we can agree upon the theoretical aspects of this single most difficult task ever attempted by the human race, namely, the adoption of a new social contract for a large number of loosely linked small communities that will replace the Former United States (FUS). The North American experiment in which a large number of (large) sovereign states were united under a constitution is over. The United States is dead. (We should write FUS instead of U.S.) I set myself the task of forging a new basis for community!

Improper religions will struggle to provide the social contract, but the social contract must come from proper religion only – not just proper religion but a minimal proper religion, so as to reduce the number of points of contention to a level for which an acceptable probability of consensus can be expected. A minimal proper religion is our best hope for a rational social contract that will be safe from the imposition of irrational religious morals.

My agenda, then, for the first five chapters of this book is to establish a philosophical basis for a social contract that, after a suitably long period of adjustment, can be adopted by the vast majority of the members of a community, which might be very tiny, or might encompass the entire human race. This social contract, then, will replace the Constitution locally and provide a guide for human behavior adequate to ensure peace, harmony, and a prolonged period of human happiness. (Procedural matters, such as the time of community meetings, might be decided by consensus on an ad hoc basis.)

Many

ecological systems are very large, e.g., the

Summary

We have solved the problem of the failure of the doctrine of separation of church and state by distinguishing two types of religions – proper and improper. Improper religions disqualify themselves from any rational social contract by their own irrationality. We have solved the problem of achieving wide acceptance for a rational community religion by postulating a certain type of rational religion, a minimal proper religion (MPR), that protects a community of autonomous people from any restrictions upon their (personal and individual) autonomy. (We intend that the members of the community be autonomous and self-governing at the individual level, not merely at the community level.) Let us now consider the construction of a philosophy that will provide a suitable basis for an MPR whether it’s considered religious or secular philosophy. (Recall the similarities in the definitions of (i) religion and (ii) philosophy.)

On Philosophy

No man who shuts his eyes and opens his mouth when religion and morality are concerned can share the same Parnassian bench with those who make an original contribution to religion and morality, were it only a criticism. – George Bernard Shaw, The Irrational Knot

Abstract

I am not a professional philosopher, nor am I particularly learned in the history of philosophical thought; therefore, whatever I do in this essay must be especially simple if I am to have a decent chance of getting it right. I am not inclined to read the philosophers of “antiquity”, which shall be taken to include Hegel and all those who precede him. Without going into specific examples – to save space, I believe they accept too many premises, such as the validity of rulers and slaves, that are not acceptable in the present era. Also, their methods of obtaining proofs seem to be inferior to the methods of the best mathematicians, such as Poincaré, Hilbert, and Lax, who is still alive. Regrettably, when I attend lectures on philosophy, I am disappointed that the speaker is interested in the philosophy of someone else, such as Leibnitz, Bentham, or Aristotle, rather than his or her own philosophy. If a professor of philosophy discusses a new point, it is usually a point that is so narrow that the outcome of the discussion is irrelevant. Presumably, professors of philosophy know what they are doing and why, but the point of their efforts eludes me – for which I make no apology. I am aware of my debt to philosophers, though, and I shall begin by borrowing from William James.

[Note in proof 9-23-95. Many months after this section was written I read Bertrand Russell’s wonderful book A History of Western Philosophy [12]. It convinced me that I haven’t missed much in neglecting the philosophers who preceded me other than John Dewey. Also, I heard about Charles Sanders Peirce [13] at a meeting of The Society for the Advancement of American Philosophy. And, of course, we have Russell himself.]

On Existence

The discussion in this section touches on existence itself. We would like to define existence in terms of primitive concepts. However, it is difficult to find a concept more primitive than existence. Obviously the word “thing” follows from existence rather than precedes it. Nevertheless, we shall use the word “thing” in deciding what exists. Following the old semantic trick, we say that everything exists provided it is not said to be something that it is not. By thing we do not limit ourselves to corporeal things.

Definition (Existence). 1. Existence is a name for all that exists. 2. Existence is a property of things that exist and everything exists unless it is said to be something that it is not.

[Note in proof (12-4-04). Consider the statement, “Some things don’t exist.” Is this a paradox that requires a sharpening of our definition of existence? The statement seems to say, “Some things exist that don’t exist” or “There exists a non-empty class of objects that both do exist and do not exist,” which is paradoxical. Thus, the thing is said to be something that it is not, therefore it does not exist. But, it was said that it does not exist, therefore it is not said to be something it is not. So, it exists. This is amusing and, perhaps, a waste of time, but, otherwise, unimportant. The correct sentence is, “Some things do not belong to the Universe or even the Ideals; they belong to our imaginations, our mythology, and/or our fiction.” This sentence is easy to parse, whereas the sentence “Some things don’t exist” is bad syntax, but otherwise innocuous.]

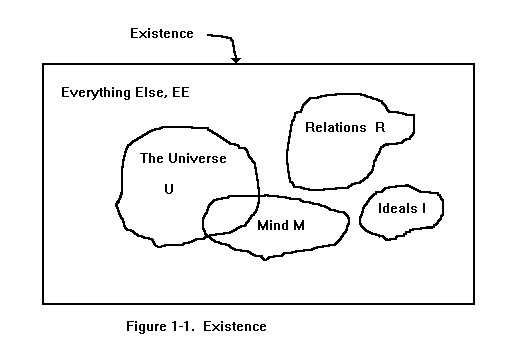

Our conception of existence is illustrated by Fig. 1-1. The thick rectangle is supposed to be the boundary of all that exists. (Never mind the finiteness, boundedness, and two-dimensionality.) We divide existence into five parts as follows:

1. The Universe, U, in space and time (with a few extra compact dimensions thrown in to account for the fundamental forces according to Grand Unified Theories). I do not know if this can be said to include all of time or not. (Sometimes only the part of U of which we are aware is referred to as the real world. On other occasions the term real world is taken to be synonymous with U. Differences should be clear from context. In my philosophy, The World, W, refers to all that exists, i.e., Fig. 1-1. Thus W = U U M U I U R U E . For the benefit of the uninitiated, I should say that the symbol in the equation that looks a little like a sans-serif U is the symbol for union; i.e., the objects represented by the letters U, M, I, R, and E are joined together and taken all together to be The World.) The symbol W, then, refers to The World in the large sense as it actually is.

[Note in proof 4-13-96. I believe I can describe a universe that includes all of time and is all of a piece. Every future event in that universe is predetermined, however no part of that universe can be said to be conscious mind. Therefore, events in mind are not predetermined. They enjoy a separate existence, which cannot alter the future of the universe in any way. Nevertheless, from the point of view of mind, the way in which it makes its decisions, i.e., its free will, makes all the difference in the world. What we think determines who we are and our relation to the universe even though it has no effect on the universe as it really is. This is good enough. I am not claiming that what I have just written is the actual case. It is only a renegade thought.]

2. Mind, M, i.e., the sum total of all mental activity and mental latency of all creatures. Mind might be a subset of the universe. I don’t know. Probably, it cannot be known. I do not require a one-to-one relationship between mind and events in the universe such as the flow of electronic currents or the migration of ions in brains even though such a relationship might exist. Mind may be a large connected set or a large number of disjoint sets. The topology of mind is not understood.

3. The realm of Ideals, I, which includes, among many other things, every geometry that could ever exist complete with every lemma, theorem, and corollary – including the correct geometry of the universe, the Grand Unified Theories, if they exist, in all their glory and for every possible world, relations in their universal sense, i.e., greater than, North of, and many other things – things that Russell calls universals. The Ideals are eternal and immutable.

4. The correct relations among things in U and M belong to the realm of the Relations, R, e.g., the distance from the tip of my nose to every other macroscopic, identifiable object in the Universe as I go on my nightly walk is a collection of relations. Of course, incorrect relations exist only in Mind or on the printed page where they are mere artifacts of the Universe. In fact, if one says that the distance from the tip of my nose to the edge of the Grand Canyon – now – is six feet, one speaks of something that does not exist – not the distance of the tip of my nose from the Grand Canyon – then – but the six-foot relation as an object in R. That relation is said to be something that it is not, so it cannot be in R, which consists of correct relations only. Notice that the correct relations are hardly ever known to Mind, first, because their infinitude dwarfs what can be known and, second, because we do not apprehend sense data with infinite precision. The relations available to our minds are only approximations to the correct relations in R, which, nevertheless, exist – unless quantum mechanics somehow makes them impossible, in which case we would replace them with quantum surrogates. This is much more than we need to know; so, necessarily, I have said more than I needed to say. Please disregard anything that seems vague or otherwise incomprehensible.

5. Everything Else, E, i.e., that in which U, M, I, and R are embedded, if it exists, whether it has dimensionality or not – something completely beyond our comprehension or imagination.

Note. The Relations (not the universal relations, which abide in I, such as to the right of, greater than, etc.) evolve in time, but whether or not all Relations for all time exist depends upon whether the Universe, for example, in all of its proper dimensions including time-like dimensions exists; i.e., not only the present exists, but the past and the future exist on an equal footing with the so-called present. This is an interesting question, which opens up inquiry into Everything Else (E), in particular, the possibility of something in which U, M, I, and R are embedded. If that “space” has a time-like dimension, U et al. would appear from the viewpoint of an intelligence living in E, which, if you remember, we know nothing about, as a complete and finished object.

Clearly, this division of existence is valid logically. It is – quite simply – a linguistic convenience, but it achieves a great deal philosophically in that it solves “the problem of God”, for example. It provides a place for God to exist without resorting to a statement such as “God is all in all”, which would be an abuse of language. It comes perilously close to being the “merest truism”; nevertheless, I believe we shall find it useful. For example, we have solved the problem of metaphysical truth, which shall arise in Chapter 3, by reducing it to semantics.

At the same time we have proved half of a conjecture I would like to present for the reader’s consideration, namely, that it is impossible to prove either the existence or non-existence of God – under any reasonable definition of God. Clearly, this proves that a non-existence proof is impossible. But, how can we prove the impossibility of an existence proof? Such a proof would be extremely useful. In particular, it would permit us to follow Walt Whitman’s alleged advice, “Don’t argue about God.”

The category of the Relations was defined to deal with the slight (or profound?) difficulty in identifying the Ideals. When first defined, these were of two types – regrettably. Type I: the eternal and timeless Ideals such as the Idea of the color blue. Type II: the constantly enlarging set of relations among things in U and M, e.g., as I go for my evening walk, the relativistic distances (intervals) between a point on my right thumb and the other objects in the Universe, the relation of every thought of one man to every thought of another. One would like to have the eternal things in a different set from the relations in the evolving Universe; however, we are getting used to regarding time as not very different from the other dimensions regardless of its “arrow”. Who knows but that some of the (compact) dimensions required to unify the forces may have arrows as well. After much deliberation, I have called the Type II Ideals the Relations. However, one wonders if all of Euclidean Geometry – complete and perfect – is a collection of relations and nothing more, in which case the categories are badly named. Let the reader decide.

Avoiding Infinite Regression

At a well-known West Coast university, a series of weekly lectures in science was open to the general public. A lecturer had just finished describing the manner in which the earth revolves about the sun. “Nice theory,” quoth an elderly woman, “but the earth rests on the backs of four elephants who stand on the back of a giant turtle.” With an appreciative grin the lecturer countered with the usual Socratic question as to what supported the turtle. “Oh, I know all about that old argument, but it’s turtles all the way down.” [Note in proof (7-20-2004). This is not a true story, probably.]

William James [11] based his evaluations of religious sentiments on his personal judgments and experience of philosophical reasonableness and moral helpfulness. Following James, I have avoided infinite regression, e.g., “turtles all the way down”, by basing my three moral axioms and my philosophical assumptions (or articles of faith if you prefer) upon my innate judgments of reasonableness and aesthetics and my acquired conception of utility, which might have originated, at least in part, from my experience of pleasure and pain. The foundation of my philosophy differs somewhat from the criteria of James, but what I owe to James is the principle that one not only can but must rely on oneself to provide a foundation for a philosophical edifice.

[Note in proof (1-1-97). When I say “rely on oneself” I refer to certain primitive judgments that are fundamentally subjective – although we may hope for a large class of human beings, perhaps all human beings, experiencing such things in a manner sufficiently similar to the manner in which we ourselves experience them. Perhaps these subjective judgments are universal in nature and we and other people will agree on important matters of aesthetics, reasonableness, and utility.]

My three moral axioms are, roughly speaking, (i) respect for the freedom of oneself and others, (ii) respect for the environment, including animals and plants, and (iii) respect for truth. From these axioms and the basic assumptions, I derive additional morals and what are commonly known as rights, i.e., certain liberties permitted by the axioms and certain entitlements similarly derived. I next define justice and finally arrive at a rational, beautiful, and practical social contract upon which we can gather a very general consensus that permits a community to function in peace and harmony essentially without government! This social contract is what I have termed a minimal proper religion.

Presumably, we are born with a sense of what is reasonable. If not, we acquire it at such an early age that it is not necessary, for this discussion, to determine how it arises. Aesthetics, too, is assumed to be given a priori, but I shall not rely on that assumption here. Then, (1) our experiences of the world, i.e., the universe, which we acquire through our physical senses, extended, perhaps, by instruments, and (2) the events that take place in our own minds, can be used to develop the ability to reason (without assuming that the real world exists; that is, we may be reasoning about things that have no independent existence). But, once we have developed the ability to reason, perhaps by studying logic, sentential calculus, set theory, Boolean algebra, or the works of the masters, we may use it to interpret our experiences as evidence of an objective world; that is, we may deduce the existence of a real world using our developed reason.

[Note in proof (3-28-95). I do not wish to argue the reality of the complementary measurement in quantum mechanics, e.g., the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) thought experiment [14]. Personally, I believe the indeterminate observable is just as real as the measured one; but, obviously, something is real – either the horizontal spin or the vertical spin.]

[Note in proof (9-24-96). Underlying the phenomena we observe lies something that has an existence independent of ourselves as evidenced by the undeniable fact that the Aspect experiments (well-known to physicists [14]) will yield the same results no matter who performs them.]

Once we have established the independent existence of the world, we may rely upon the evidence of our senses and our consciousness to develop a sense of utility enhanced by our comprehension of pleasure and pain. Our comprehension of pleasure and pain is based, in part, on our sense of aesthetics, which we assumed was given a priori, but which may be enhanced by experience and other factors. We are now in possession of the three tools, namely, reasonableness, aesthetics, and utility, with which we will evaluate philosophical assumptions and moral axioms. I hope that I am not an anomalous specimen of humanity, but that my primitive notions will be experienced by most, if not all, of humanity.

Once the moral axioms have been stated with a sufficient degree of rigor, a system of morals can be derived from them that can serve, in turn, as a basis for human rights and for the rights of other creatures. Justice is based on morals and rights. Thus, morals are based on aesthetics, reasonableness, and utility; rights and justice are based on morals; and our knowledge of the world, including our knowledge of the usefulness of things, is supposed to come from experience and reason. What we choose to experience or apply our powers of reasoning to, and how we decide to take the next step in our reasoning may be dictated by our imaginations or other faculties, which might include intuition, a faculty that is presumed to come primarily from experience. It is not necessary to suppose that the origins of intuition are well understood. We do not necessarily deny the existence of divine inspiration. If the conclusions based on the moral system derived from the fundamental assumptions and the moral axioms lead back to reasonableness, aesthetics, and utility, we will have developed a consistent philosophy. I do not see how we can hope to do better. If some future generation accepts it as a minimal proper religion suitable for a social contract upon which a cooperative society such as the one described in this essay can be based, the most improbable dream of a dreamer of impossible dreams will have come true.

I shall give a list of philosophical assumptions, which might as well be called articles of faith. I hope that I do not assume too much. This essay is supposed to be an example of the axiomatic methods of science applied to human society. Normally, if an axiom is required to prove what we already believe is true, we simply go ahead and assume it. For example, most of modern mathematics rests on the Axiom of Choice, which makes claims about what would happen in a process that takes place an infinite number of times, namely, the selection of one member from each of an uncountable number of nonempty sets [15]. Naturally, the axiom cannot be verified experimentally; moreover, it might be possible to derive an entirely different mathematics by assuming that the Axiom of Choice is false. I cannot imagine what would be gained by devoting volumes to determining which is the case even if it is possible to do so. [I believe that it is not.]

I hope that this development is adequate, but, if it turns out to be deficient, I will add whatever else I need to construct this system, which appears to me to be nearly complete according to my intellect and my intuition. These ideas came to me in chronological order, i.e., in the only way in which anything comes to anyone, rather than in logical order, so I must search constantly for errors that may have arisen in the reordering process that occurs when one thinks and writes. This is an important point, which, it seems to me, is frequently overlooked, namely, that we do not present arguments in the order in which they occur to us. One of the ramifications of this may account for our unwillingness to abandon our most cherished notions.

Reasonableness and Aesthetics

Reasonableness is very much related to our sense of aesthetics. Musicians say that a beautiful passage “makes sense” and mathematicians say a reasonable argument is “beautiful”. Perhaps the part of our being that receives pleasure from things aesthetic is identical with or similar to the part of our being that finds satisfaction in things that make sense. It is possible that, if they are not identical but rather two parts of ourselves, they are mirror images of one another, one on the right side of the brain, the other on the left. (Since the right-brain / left-brain theory is unproved, hereafter I shall enclose the terms in quotes to indicate the provisional and figurative nature of the terminology. I do not need to inquire into their mechanisms to identify them categorically or definitionally, but I would like to inquire, briefly, into the origins of our sense of beauty and our sense of reasonableness so that I can depend upon them as a guide for philosophical judgments.)

Are we born with a sense of aesthetics, which, for me, is the same as the sense of beauty? If so, are we born with a sense of what is reasonable? If we are not born with them, do we acquire them early in our lives in an infallible way upon which we can depend with as much certainty as if we were born with them? In the introduction to The Critique of Pure Reason [16], Immanuel Kant claims the existence of a priori synthetic judgments, however the examples he gives do not seem to be valid – in my opinion. The first example is mathematics, which as I have noted below, is essentially definitional and, therefore, analytic, as opposed to synthetic. [Note in proof. The definitions from which mathematics is derived by analysis are synthesized, therefore I am not sure to which category mathematics ought to belong.] The second example is the judgment that every effect has a cause, which might be discredited by the quantum theory. Thus, Kant ends up by trying to determine the properties of a class of objects which may not have any members.

But, if any form of knowledge could be both a priori and synthetic, it seems that it must be our sense of beauty. As far as we know, the beauty of an object cannot be deduced from it by analysis (although probably some scientist or artist is trying to discover how to do it); moreover, it seems that it is not given by experience either. Thus, if I do not misapprehend Kant’s intention, our sense of beauty must be an a priori synthetic judgment. It remains only to determine that our sense of beauty, for example, is what Kant meant by a judgment or a faculty of judgment and I must assume that it is. On the other hand, if Kant would exclude the sense of beauty and the sense of reasonableness from his category of a priori synthetic judgments, his category might be empty, which, of course, is of absolutely no importance.

In this essay, I do not appeal to the idea of a conscience. If the conscience is, in whole or in part, the residuum of notions picked up in our earliest years, before we were able to apply our judgment, then, conceivably, a portion of it could be confused with aesthetics. We might judge that something, e.g., sex, is not beautiful because we have retained an irrational notion that it is not beautiful from notions picked up early on that are in conflict with what we would decide had we been left alone. We would like to distinguish conscience as a negative attribute in contradistinction to aesthetics and reasonableness, which we hold to be natural and desirable. This is a mere semantic quibble and should not cause any difficulties.

Similar reasoning can be applied to our sense of reasonableness. I am not referring to the science of logic or to the theory of sets. In order to acquire these systems of thought one must already be in possession of a sense of reasonableness or one would not be able to turn the first page without throwing up one’s hands in disgust or despair. We understand the fundamental premises of these systems of thought because we are given a sense of what is reasonable a priori. Moreover, the reasonableness of something cannot be deduced from its other qualities without having in place the mechanisms of thought upon which analysis is based and these mechanisms must follow from our sense of what is reasonable. Piaget [17] has given evidence of developed reasoning ability in very young children, who, presumably, are not in possession of a calculus of reasoning such as set theory. I do not know the position of modern child psychology on when the rudiments of reason can first be observed in infants.

We begin to experience the real world (the objective universe or, at least, the part of it of which we are aware) through our senses before we are able to deduce its existence. Also, we are aware of events occurring in our own minds whether we consider them a part of the real world or not. We take advantage of these experiences, which might include our educations, to develop our innate reasonableness into an ability to reason. We are able, then, to deduce the existence of an objective universe from the evidence of our senses. Since I will not give the steps in this deductive process, I will assume the existence of the real world as an article of faith.

Note:

Despite the results of the Alain Aspect experiments to test

Utility

Our experience consists of our perceptions of events in the world through our physical senses and the events that occur in our own minds, which we interpret as joy, sadness, pain, love, anger, hate, compassion, nostalgia, etc. We are endowed, too, with memory. The faculties with which we are endowed permit us to develop our primitive sense of reasonableness into an ability to reason, which, in turn, permits us to deduce the reality of some sort of objective universe – regardless of our position in the Einstein-Bohr debate, if we, indeed, have such a position. Our initial experiences and impressions of existence come far in advance of that deduction and, without reasoning, cannot be presumed not to be delusions. Given an objective reality, which includes our own existence and the events that occur in our minds, we are in a position to judge the usefulness of objects and institutions that spawn events of a predictable nature. Since we believe in objective reality as a collection of events and we believe in ourselves, we are not in doubt as to the meaning of experience. Utility, then, is judged in terms of experience and how we perceive pleasure and pain, that is, in terms of our sensibilities. We may exercise our sense of aesthetics, too, in evaluating usefulness. I do not wish to explore the role played by experience in the development of our sense of aesthetics. It may be similar to the role played by experience in the development of reason, but, since I do not claim that our sense of aesthetics has developed into anything new (such as artistic infallibility), I do not need to explore that subject further.

We now have a complete basis for judging values, philosophical assumptions, and moral systems, namely, (i) aesthetics, which is presumed to have been given a priori, (ii) reason, an outgrowth of our primitive sense of reasonableness, and (iii) utility, which is based on experience of the real world. We can construct a basis, then, for deciding what else can be known and for evaluating new knowledge, but we should be aware that the basis rests on assumptions that may not be correct.

Occurrence Implication and Occurrence Equivalence

In mathematical logic, letters stand for simple statements. For example, the letter A might stand for “It is snowing” or “All governments are bad” or “Smarty Jones is a dog with two heads” or “All horses have five legs”. In the statement “It is snowing”, one wonders what or who “It” is. The sentence could have been replaced by “We have snow” or “There is snow” or, simply, “Snowing”. The symbols A → B are read normally as “A implies B”; however, all of the following are equivalent: (i) A implies B, (ii) B if A, (iii) A only if B, (iv) not-B implies not-A, (v) B is a necessary condition for A, (vi) A is a sufficient condition for B, (vii) if A then B. By the symbols A ↔ B we mean: (i) A implies B and B implies A, (ii) if A then B and if B then A, (iii) A if and only if B, (iv) A is a necessary and sufficient condition for B, all of which express the fact that (v) A and B are logically equivalent.